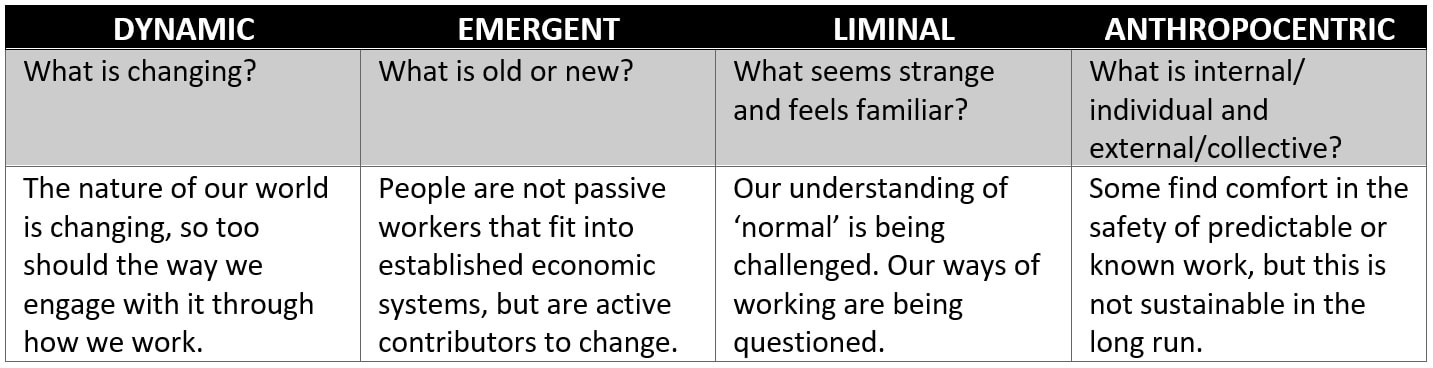

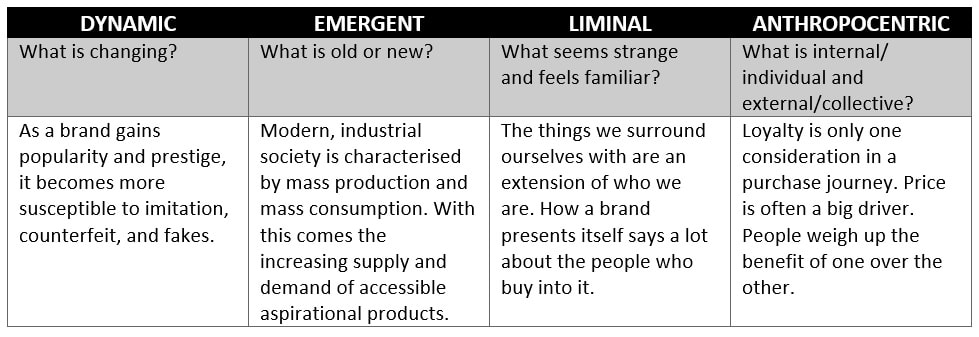

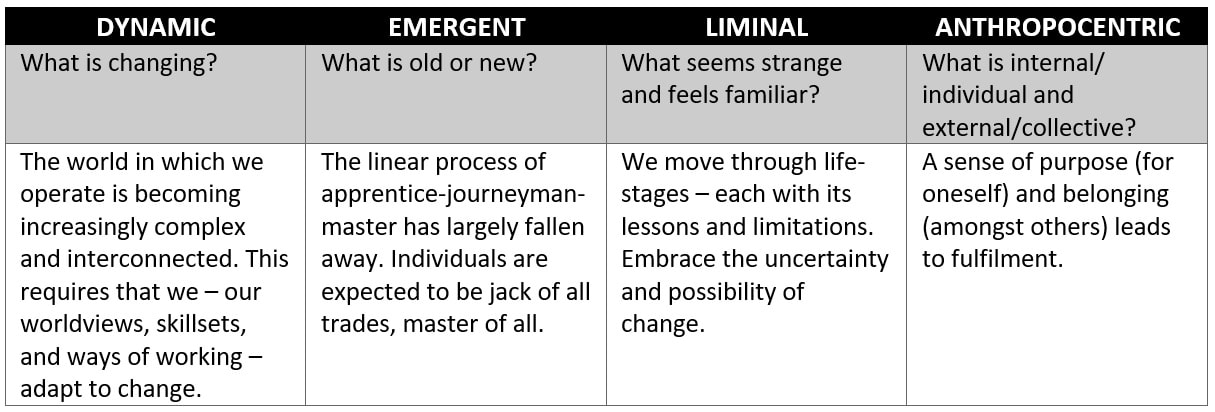

What if our professional legacy is dismantle old ways of working? Creative Destruction If we have learned anything from this pandemic, it is that our sense of ‘normal’ was somewhat warped. While many long to return to ‘normal’, some say we are heading for a ‘new normal’, and others argue we should prepare for a ‘post-normal’. Just as a relationship cannot return to what is once was when a partner betrays another’s trust, or how a person’s status (and arguably their life) is forever changed once they become a parent, so too can businesses not fall back into old habits, outdated ways, or dead ideas. “We can’t blindly accept what’s presented to us as normal,” said a participant at this year’s Global Business Anthropology Summit. Although it is a difficult sell convincing a legacy team of the changes needed – not just in practice but in mindset too – herein lies the promise of a better tomorrow. It is in the ritualised negotiation of ways of working that change manifests and sustains an organisation moving forward. Living in a DELA world Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter first formulated the term ‘creative destruction’ in 1942; a time nearing the 3rd industrial revolution and at the height of the Second World War. He described it as: "the process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one." While this is often associated with the development of capitalism, it could be useful in its application when thinking through our own ways of working today. Especially considering that we find ourselves at a similar pivotal moment; entering the 4th industrial revolution and situated in the middle of a global crisis. We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that is unfolding, and to shape our own narrative going forward. Our world requires a deliberate dismantling of oppressive, exclusive, or passive practices, to allow for an emergence of improved, inclusive, and active processes. We need to commit to making shifts in our business spaces, realms of work, or spheres of influence; even if just incremental change, it matters. We need to break free from the constraints of normal. This was originally published on Marklives

0 Comments

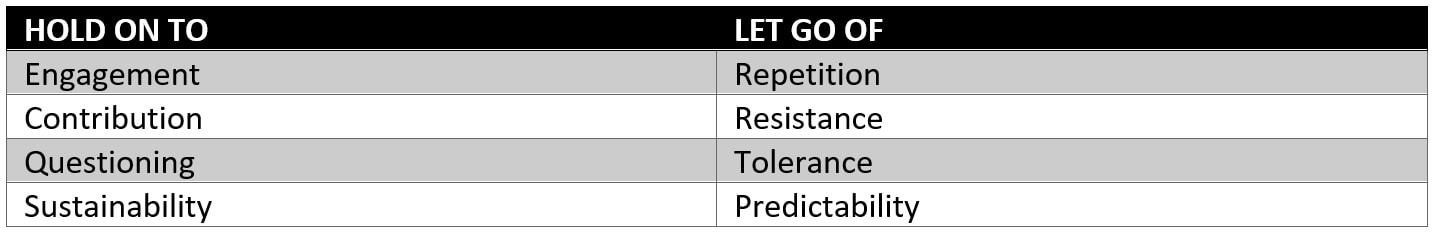

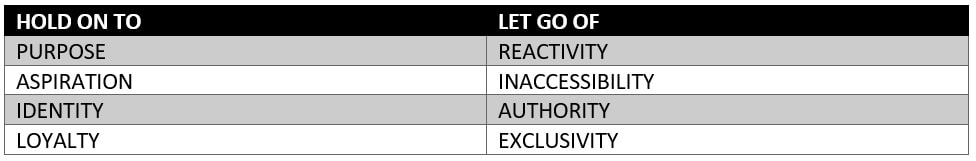

What if we viewed competition as a motivation, not a set-back? First with your head, then with your heart Counterfeit, imitation, fake. A nightmare for any brand, especially a small business that lacks the means to fight back. This was the reality earlier this year for a South African clothing brand. A family business spanning generations and built on the purpose of delivery bespoke apparel to an exclusive audience. This was not a contender in the same weight division as Nike, Adidas and the like. What seems to happen, as the brand gains popularity and prestige, it becomes more susceptible to imitation. A futurist, Xolile Martin, had been offered a counterfeit of this local brand’s products. It was being sold in China Town malls and online platforms such as Facebook and Whatsapp. He alerted the brand of the fakes circulating at a fraction of the original’s cost. Understandably, the brand was shocked. The challenge seemed impossible to tackle. They decided to take a legal approach; warning its online audience of fakes, announcing their collaboration with authorities, and encouraging people to only buy through official channels. Living in a DELA The commodification, fetishisation, and appropriation of culture is a delicate, entangled, thorny problem. Essentially, brands create and shape culture – in terms of behaviour, values, aspirations, identity, and more. For those who are deeply rooted in legacy or have strong heritage connections, this requires further consideration and contemplation for how one disruption, change, or intervention could impact an entire ecosystem in which it exists. We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that is unfolding, and to shape our own narrative going forward. Rather than fighting against something, brands have the choice to fight for something; to create a new consumption space, to tap into another audience, and to draw on localised trends. This is an opportunity to connect with people and ideas in a way that builds long-term relationships, calls them to action, and instils a sense of collective purpose behind a shared vision. Originally published on Marklives

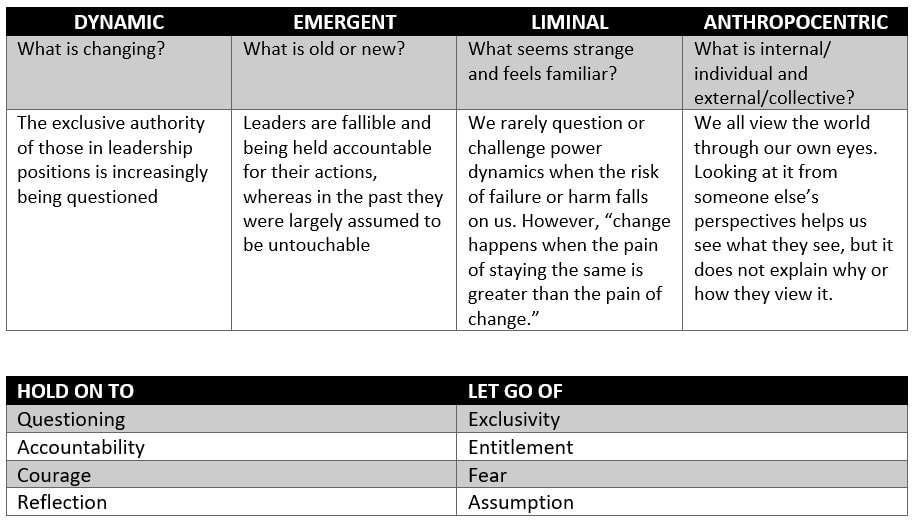

When things go wrong inside organisations, simply replacing one leader with another will not facilitate the systemic change needed. The corporate world is filled with predator-prey relationships where one benefits over the other. A colleague in a foresight-based writing programme, Fazidah Ithnin, shared a Malaysian proverb; it is like saving us from the crocodile and throwing us to the lions. How do we nurture the forest instead, creating an interdependent ecosystem for all involved? Living in a DELA world How does anyone obtain success these days? It is no longer a question of who you know, but rather who knows you. How do you build that reputation and network? Where do opportunities for growth, progress, and reward even come from? Is it worth the sacrifice we make just to be seen, heard, or considered? We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that is unfolding, and to shape our own narrative going forward. We are quick to place the blame on leaders as individuals and forget that they operate in a bigger context that supported them in obtaining this position of power. By incorporating a culture of questioning norms and challenging the status quo, we can encourage organisations to learn and adapt as they go. Leaders are intended to be representative of the whole, and to guide the collective on a journey towards a shared vision. They are neither above nor outside of but very much part of the system. It would do a whole lot of good for businesses to function as safe spaces for taking chances, distributing consequences, and changing without pain or punishment. As a Eugenio Molini of GAIT says, we can start by respecting ourselves, empathising with others, and being considerate of the whole. First published on Marklives

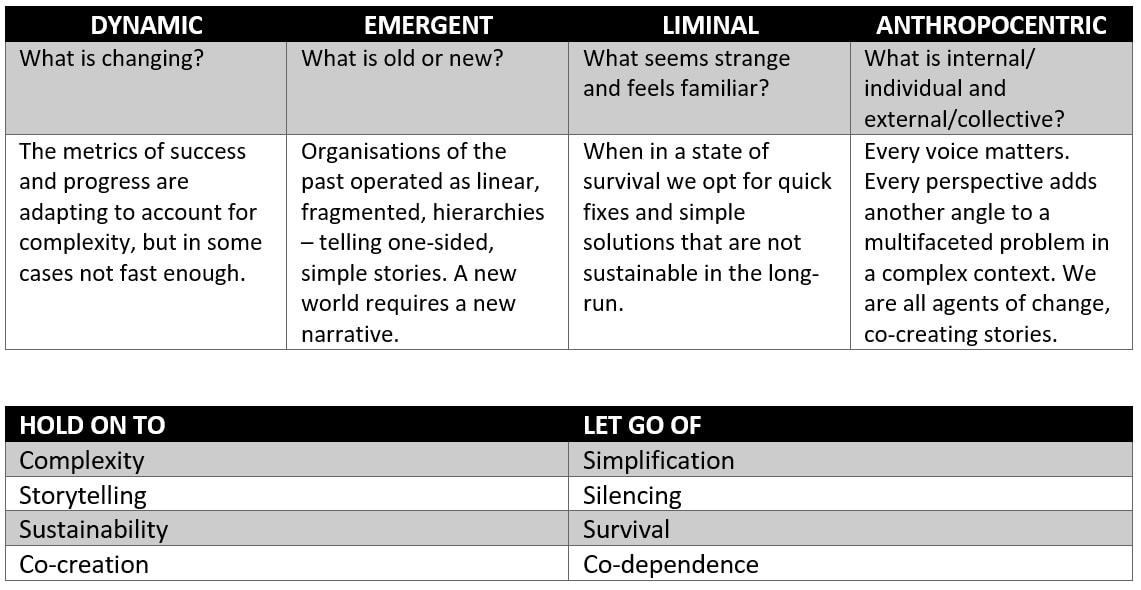

What if we light a spark of change and spread it through an organisation, making new with fire something old and dying? The trap of simple stories In a recent series of exploratory sessions hosted by management consultancy Cognitive Edge, a conversation about simplicity and simplification was brewing. Essentially, when faced with the unknown, we tend to simplify. It is easy to gain control in this way — or at least the illusion there of. But at what cost? Sonja Blignaut, complexity and narrative consultant and thinking partner, raised a point about the mindtraps identified by Jennifer Garvey Berger, leadership coach and author. The mindtrap in question was that of simple stories, “when our instinct for a coherent story kills our ability to see a real one”. Simple stories simply don’t work in complexity. Humans are complex beings, we operate in complex systems, and we live in complex times. So why do leaders often claim clear connections between cause and consequence? For example, if employees are looking to get raises, promotions, bonuses or other forms of rewards and recognition, they are often provided with an unobtainable, seemingly simple path to progress. However, the metrics used to measure their performance don’t take into consideration all that they do beyond their job descriptions; they ignore the complex inner workings of an organisation that can’t always be captured in words or on paper; and they reduce an intricate human being to a mere cog in the machine. Progress is near impossible. Danger of the single story It’s been 12 years since TED released Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s The Danger of a Single Story. Her wisdom continues to ring true. The stories we tell hold power. “Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person,” said Adichie in this talk. We need to be careful not to flatten several stories into an overarching, generic one. This is how misunderstanding and miscommunication happen. In a business setting, it’s equivalent to limiting people to an identified role or strict set of responsibilities against which they are judged and their progress determined. Stories should also not be one-sided; they need to be collective, collaborative and ever-changing. In the corporate world, this means having open and honest conversations across departments and domains. Living in a DELA world There’s a term in isiZulu that captures the idea that, if something happens too easily, it’s suspicious. It’s too good to be true. Quick fixes and simple solutions are not sustainable in complexity. Umlilo wamaphepha: paper fire. When you light a newspaper, it goes up in a brilliant burst of flames but it’s short‑lived. We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that’s unfolding, and to shape our own narrative, going forward. How do we ignite a spark of change and spread it through an organisation? According to Dave Snowden of Cognitive Edge, it’s not about creating better versions of old things but rather implementing symbiotic strategies. Take a small aspect of something that already exists and make it new — this makes change more attractive and less threatening. Originally posted on Marklives

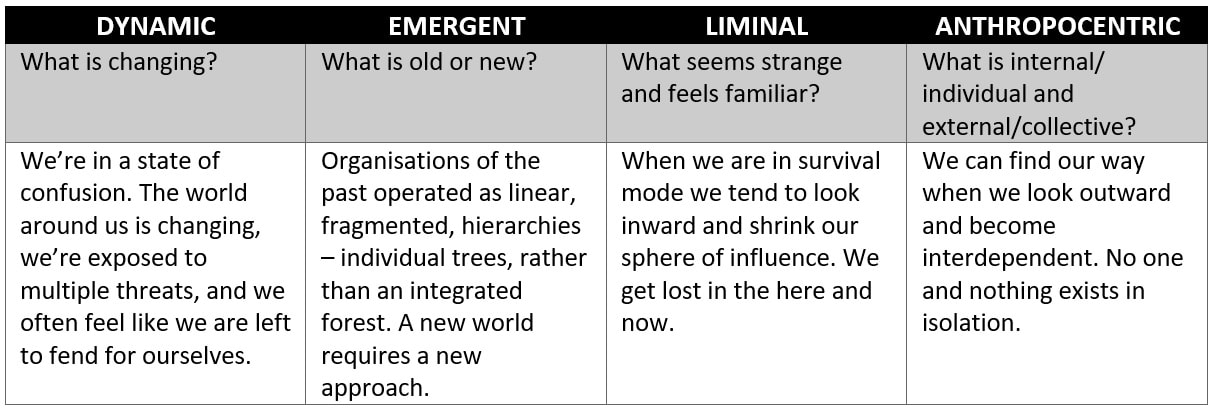

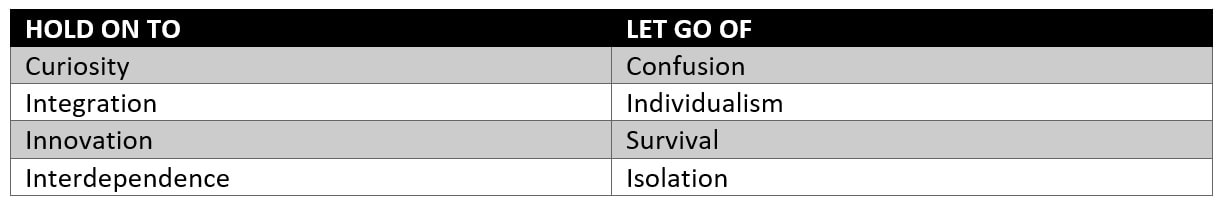

What if we shift from a parasitic-type interaction to a mutually-beneficial symbiotic relationship? From enlightenment to entanglement Organisations are like forests. At first, it was assumed that trees operated in isolation — much like employees in silo roles or departments —placed in a competitive environment, seeking space and resource. Because it was assumed that they functioned independently, it was accepted that they were indifferent to one another — both trees and employees, that is. Ecologist Suzanne Simard uprooted this naïve notion. She found that, in addition to conflict, there’s also negotiation, reciprocity and even selflessness. Much like an iceberg conceals its mass in unseen depths, so do trees in a forest have hidden elements. In particular, there are underground mycelium networks, a tangled web of roots through which communication and resource transfer occur. Enchantingly, the forest behaves as a single entity. So, too, should an organisation. The Giving Tree As with any network or community, there are nodes, links and interactions. In a forest, older trees use their height to protect young saplings from harsh weather. They’ve even been shown to reduce their root size so as to make room for their growing offspring. Trees are even capable of sending warning signals to alert their community of approaching danger. When a tree dies, they pass on their knowledge and provide sustenance for the next generation of trees. Not only does this demonstrate their ability to recognise their kin and distinguish between threats, it shows how they depend on one another for survival. Arguably the biggest threats to forests are deforestation, erosion, and fire. What is the equivalent to these in the world of business? What do we fear and how do we respond? Will our network protect us from unemployment, demotions and burnout? Living in a DELA World Sometimes, we get so caught up in the minor and finer details — focusing on what’s right in front of us — rather than taking a step back and noticing the bigger picture. We forget that each of us plays an integral role in the operating of the whole. We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that is unfolding, and to shape our own narrative going forward. If too many trees are removed from a forest, it could reach a tipping point and the whole system becomes at risk of collapsing. So why is it, when we find ourselves in a state of confusion — such as a global pandemic — that we remove the pillars which sustain an organisation? Rather than drawing on collective knowledge, insight and resource, we reduce, retrench and rewind. Simplified forests lack complexity and so they’re even more vulnerable to collapse. What can we learn from natural ecosystems in the way that we conduct business and respond to business challenges? How do we more effectively communicate with one another and depend on each other for survival? Certainly, hierarchies have created clarity of authority and control but they also leave little room to breathe and grow. It's in letting go of confusion that we open up a world of possibility; through curiosity, we turn our fear into motivation. We can explore new ways of working — within the safe space of an integrated system — with the freedom to innovate beyond simply surviving the here and now. Interdependent relationships create balance, connection and community, rooting us in an entangled network. Originally published on Marklives

What happened to the journey, the one where a career was an unfolding process? It’s the journey, not the destination

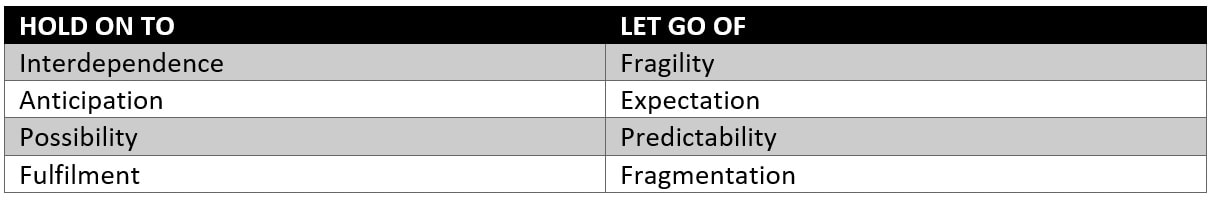

It’s rare to find such an operation in present-day workscapes; it’s more likely that an individual will enter into a position they desire. There’s very little room to move or improve here — chances are the organisation is hiring to replace, rather than upskill to promote. There’s an element of familiarity and trust that comes from looking within, as well as possibilities of jealousy and homogeneity among colleagues. Looking outside could bring in diversity of skill and mindset but also requires taking a chance on the unknown (more pros and cons here). Be a unicorn in a field full of horses How many employees have been placed in t-shaped talent moulds? The expectation that each person should “reach across disciplines, provide support in a number of situations and [have] an extraordinary expertise on a particular subject”? How about square-shaped? “What’s better than knowing a little about a lot and a lot about a little? Knowing a lot about a lot.” Or even tree-shaped? Expansive skills rooted in a depth of knowledge. How many job-seekers have been stuffed into unicorn costumes (not literally, of course)? The illusion of rarity and value. It’s no longer enough to show promise and potential; we now, apparently, need to be these mythical, magical beings. A counter argument offered says “unicorns don’t exist. Instead, look for sea otters… Why sea otters instead of unicorns? Because they are rare (and currently endangered), but if you look hard enough and create the right environment, you can find and nurture them.” Not a fan of sea otters? How about a zebra? “Zebra companies are both black and white: they are profitable and improve society. They won’t sacrifice one for the other.” In short: it’s a zoo out there. Living in a DELA world In this mystical world of make-believe, where the perfect employee, employer, and organisation exist, how do we, mere mortals, respond? We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that’s unfolding, and to shape our own narrative going forward. Because of the rate and extent at which the world of work is changing, it often requires that we adapt in unexpected ways. We need to be imaginative and innovative. Craftsmanship, expertise and specialisation take time — time that we don’t necessarily have if we wish to keep up and stay relevant. However, some level of depth and extent of breadth is needed to remain adaptable and resilient. In trying to place constraints on ourselves or people we work with, we restrict the potential of what might have been. How do we know what is needed or who is best suited? How do we evaluate and measure probability? What if the reward of fulfillment outweighs the risk of playing it safe? What if we let go and let ourselves and others be? In letting go of the fragile and fragmented systems on which our organisations are built and people are employed, we create an environment in which interdependent, fulfilling relationships can surface and be sustained. Shifting from expectation (something ‘will’ happen’) to anticipation (something ‘could’ happen) makes us more open to change. Letting go of our human need to control and predict the unknown, we can add a little magic and mystery to our work lives. Originally published on Marklives

WAITING FOR REDEMPTION

As with every plot twist, a story usually has elements of foreshadowing that precedes the change and it also unfolds in seemingly unexpected ways. It also carries the characters through on a new path. I wanted to capture the state of the world from an African perspective. A song by Johnny Clegg and Savuka came to mind: Dela. I recall in a radio interview once, Clegg explained the inspiration for the song as having come from the joy in seeing something beautiful when everything seemed so bleak — such as a yellow flower growing through a crack in the concrete pavement. LIVING IN A DELA WORLD

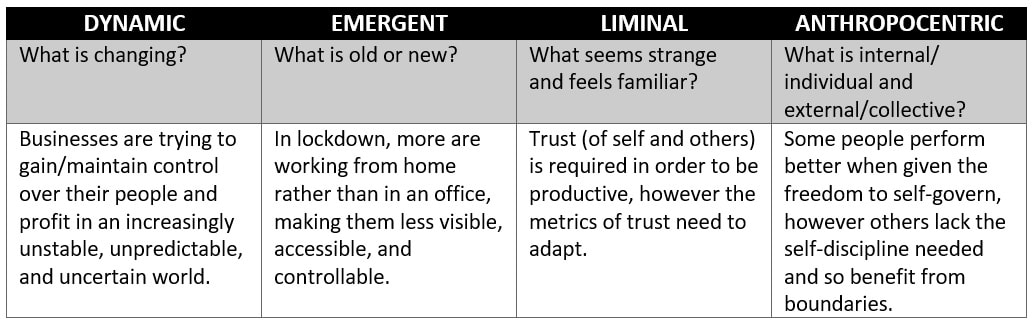

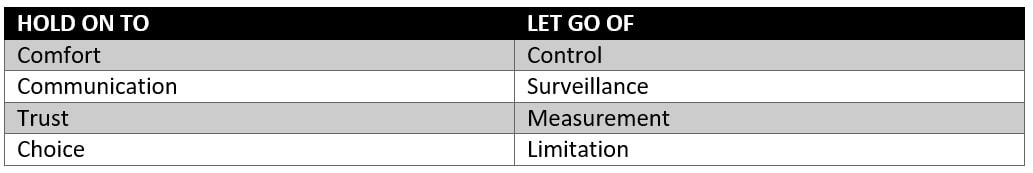

Once we know where we are, we can determine where we want to be and figure out a way of getting there. In other words, we need to tell our own story. In isiZulu, “dela” has paradoxical definitions which seem fitting for a narrative of our times: “to be satisfied” or “to have had enough” on the one hand, and to “abandon”, “give up”, or “sacrifice” on the other. In applying this perspective, we can answer the following questions: • What are we satisfied with? (What do we have enough of?) • What are we willing to sacrifice? (What do we need to let go of?) I think I know why the dog howls at the moon In ongoing conversations with friends and colleagues who’ve been employed by companies throughout lockdown, a shocking common thread emerges: they are like caged birds, confronted by their conditions of ‘captivity’, and longing for their freedom. Just as the caged bird sings in order to cope, many employees are performing beyond expectation — whether it’s to prove their worth to their employer, or to feel safe within the confines of certainty as the world around them unravels. By applying the DELA framework, we can make sense of this observation. In short, businesses are trying to gain or maintain control over their people and profit in an increasingly unstable, unpredictable, and uncertain world. This trend is amplified by lockdown as more are working from home rather than in an office, making them less visible, accessible, and controllable. Several employers are applying outdated metrics of trust, and so employees are less motivated to produce meaningful work but are expected to be highly productive. This isn’t to say that ways of working need to be scrapped and entirely replaced, or that one approach is better and suitable for all. Some people perform better when given the freedom to self-govern, while others lack the self-discipline needed and so benefit from boundaries. In letting go of the need to control our circumstances, to make visible people’s actions, to measure progress through profit, and to place limitations on what is possible or acceptable — we can find comfort in our rituals and routines, create open channels for communication, build mutual trust, and respect people’s freedom of choice. Originally published on Marklives

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed