|

Our taste preferences and perceptions differ vastly from how others experience taste. Not only do taste trends come and go as we are introduced to new food products, regional variations, and flavour innovations, our preferred tastes change as we age. As marketers, we need to incorporate verbal, visual and experiential perspectives when marketing taste. The single sip Blind taste tests are a popular way for competitor brands to determine which brand consumers prefer — solely based on taste. Products are placed in unmarked containers and given to consumers to taste and indicate which they like most and for what reasons. It isolates consumer perception and preference around taste, avoiding other influences inherent in branding. Sensation transference is the impact on taste by consumers’ subconscious associations with branding and packaging. In other words, we eat first with our eyes. We transfer the way a product appears over to our perception and experience of its taste. The Pepsi Challenge — an ongoing marketing promotion since 1975 — has consumers taste unbranded Pepsi and Coca-Cola. This challenge has revealed that most American consumers prefer the sweeter taste of Pepsi. But there is a twist to this tale: other studies have shown that, while consumers are more likely to prefer a sweeter option when allowed just a single sip, they would opt for a less-sweet alternative when drinking a larger amount over time. The taste mistake In an attempt to replace the original recipe with something sweeter, Coca-Cola introduced “New Coke”, which later became “Coke II”. ‘The new taste of Coca-Cola’ was considered by many as a major marketing failure. The original Coke formula was then reintroduced and rebranded as Coca-Cola Classic. There was a significant spike in sales, causing consumers and critics to question whether it all was just a marketing ploy or truly a cautionary tale. In 2016, Coca-Cola launched its “Taste the Feeling” campaign, shifting from a lifestyle brand to focusing more on its unmatched taste. For many, the taste of Coca-Cola is unbeatable — partly because of the powerful, subconscious and emotional experiences evoked when drinking Coke. Coca-Cola’s new campaign is particularly targeted at lapsed consumers, reminding them of the nostalgic and youthful associations they may have with the brand. The taste of place Terroir is described as the characteristic taste and flavour of a product that has been influenced by the environment in which it was produced. These include physical factors and practices involved in its production. Terroir impacts the perception and price of a product, particularly in wine, cheese, pork, cognac and coffee. There exists a relationship between taste and place. We see this clearly in single-origin coffees such as those served at Starbucks. Sourcing coffee beans from an isolated region seems to intensify the characteristic taste unique to that location. When marketing taste, we need to develop a strategy that is both appealing and that creates the impression of benefit. The challenge is to do so through justified claims and without making comparisons: a product needs to stand for the best. Edible products need to be portrayed as both tasty and flavourful in order to convey enjoyment, to be memorable and connect with consumers’ existing memories, and to be perceived as being beneficial in addressing a need or desire. This article was published on Marklives

0 Comments

Sometimes something just feels right, whether physically or emotionally. Yet researchers and marketers are only recently beginning to untangle the intricacies of feelings, desires, inclinations and intentions — and what implications these might have on the individual and collective experience. Don't touch The sense of touch is embodied in our engagement with the world. We use our sense of touch to judge the quality of a product: its weight, texture, strength and temperature. Based on consumers’ preferences of these qualities, we make particular judgments which influence our purchase behaviour. In a time of growing online shopping, marketing the sense of touch becomes limited and challenging, and marketers look for creative and innovative ways to draw on the symbolic connections that touch establishes between products and consumers. Apple’s packaging is often considered to be part of the product as it adds to the overall brand experience. Apple has taken this a step further in the development of its concept store, where consumers are able to experience the brand more holistically — they may hold the product, try it out, listen to music, and examine it in person. Coca-Cola’s familiar bottle shape is a prime example of ergonomics (the design of a product to be both functional and comfortable for human use). The bottle has been designed to be held comfortably, but also to be recognisable as unmistakably part of the Coca-Cola brand. With feeling In marketing, affect (to move emotionally) often leads to effect (to bring about change). To feel is to experience something; to have sense and sensibility. It is a shift from consciousness (feeling experienced the mind) to action (feeling embodied). In a world of uncertainly, distrust and change, consumers are drawn to brands that represent honesty, transparency, upliftment and authenticity. Messages of empowerment and inspiration are welcomed and positively received. #LoveHasNoLabels was a campaign that challenges people to acknowledge and remove the prejudices they might have towards others, based on the labels they place on them. It called for a move away from judgment, stereotypes and generalisations. It did this through an interactive campaign that demonstrated — with the use of an x-ray screen — that the labels we place on each other have no physical grounding. It was an emotive campaign that moved people to re-evaluate their own perspectives, opinions and views of the world. The challenge for marketers is to draw on consumers’ feelings — both in the physical and emotional sense — to create a holistic experience in which they can immerse themselves and to connect with brands in a real, authentic, and tangible way. This article was published on Marklives

Do you remember — when you were a child — the scent of new clothes in the New Year, wrapping paper and cake candles on your birthday, freshly baked bread in a local bakery and newly cut grass on weekends? Do these scents remind you of moments, memories or emotions even now? When I was a child, South Africa smelled like bushfires, laundry detergent, Zam-buk and KFC. Now, when I drive past a burning field, hang up the laundry, get sunburnt or order takeaways, I am transported back to my childhood here. Unscented Aromas tend to conjure up childhood memories because we encounter most new scents in our youth. When we first come across these aromas, we forge a link between scent, memory and emotion, and these links form part of our episodic memory. Episodic memory refers to the events in people’s lives that are subjective, personal and relative to the individual. Scent marketing draws on episodic memory to enhance or establish particular associations consumers might make with certain products or brands. The challenge for marketers is to create memorable moments and emotional links between the consumer and a brand or product. Because particular scents are lodged in our memories with deep-rooted associations, scent marketing is an effective way to draw and build on these existing connections. Two big brands, New Balance and Mercedes Benz, appear to have gotten it right — but in different ways — by tapping into the two categories of scent marketing: ambient scenting and scent branding. Ambient scenting Ambient scenting fills the air with a particular scent in order to influence the consumer experience within that space. In other words, it adds to the experience of walking into a place — whether it is estate agents brewing coffee before an open house to create a feeling of home and warmth, or barbershops spraying cologne to create a refreshing and sophisticated atmosphere. When the New Balance shoe store opened in Beijing in 2009, it understood that “it’s no longer simply enough to present or provide your products or services in a strongly branded visual context; the brand needs to connect and engage with all five senses of the customer in order to create resonance and establish long-term loyalty.” The New Balance store brought in notes of wood and leather to convey ‘heritage and craftsmanship’ by imitating the aroma of a mid-20th century shoe store. Results reflected the success of doing so, as customers seemed to spend more time in the store. Scent branding Scent branding is about creating a signature scent that is associated with a brand and evokes certain emotions. It draws on “social developments, cultural movements and sociological changes” — something futurologists at Mercedes Benz are very familiar with. By looking at past and present patterns, it was able to pinpoint what is and will continue to be important for its core target group and then, together with a team of olfactory experts, created a signature scent that reflected that. This article was published on Marklives

As marketers, we sometimes underestimate the power of sound. It is so much more than background noise; it is rhythm and rhyme with reason, melodic moments that trigger memories, soundtracks to shared experiences, and a sonic space we live in. Soundscapes We live in a world of sound. We are alerted by alarm clocks, car alarms, police sirens. Our mood is influenced by soothing sounds of rainfall, eerie background music in scary movies, aggravating sounds of people chewing or clicking pens incessantly. Our memories are invoked by Christmas carols, love songs, nursery rhymes. We live in a realm of sound that we experience differently from one another. We construct sounds; imagine them; experience them; and process them. We create our own soundscapes. Culturally, oral tradition depends on memory: it enables people to recall and remember stories, events and information. Sound here is a device used to store and recover verbal data. Social scientists are able to trace thought patterns, reasoning frameworks, information transfer systems, and knowledge-preservation techniques by looking more closely at a community’s oral traditions — its music, storytelling, and verbal teachings. The challenge for us as marketers is to construct soundscapes that are relevant to the consumer’s sociocultural contexts. Here are some examples. Fueling associations Several are harnessing the excitement and unexpectedness of flash mobs. There’s been several, and they’re well-documented on YouTube. Locally, an Engen garage in Cape Town surprised motorists with a flashmob performance of a popular local song, Burn Out by Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse. It used, to its advantage, the already-favourable associations people have with this song to create a shared experience of sight, sound and performance. Effective echoes Have you ever heard that syncopated rhythm of pop, pop, pause and been able to identify it as the unmuffled rumblings of a Harley Davidson? It is a trademark sound that we immediately associate with a brand before we even see it. It triggers a specific association and evokes particular responses when we hear it. Marketers sometimes refer to this effect as the ‘sonic boom’ — the ability to connect with a consumer through the use of sound. The Sound of Porsche made use of this sonic boom in its innovative sound-driven campaign that allowed consumers to interact with the brand in a new way. Evoke emotions & invoke ideas Music is often used as a tool to evoke emotional responses, or to invoke physical reactions. On a quiet night, a restaurant might play slow music to relax consumers and encourage them to extend their consumption. During a busy shopping time, some stores play up-tempo music to create a chain reaction of sped-up purchases, shortened queues, and increased volumes of shoppers. For many South Africans, Johnny Clegg’s music is the soundtrack to our lives. We are instilled with a sense of pride when Impi echoes in the rugby stadium; we tear up when we hear Great Heart and are reminded of the movie Jock of the Bushveld; we crave a beer when we hear Osiyeza (The Crossing), and we mourn our troubled past when we hear Asimbonanga — a song written for Nelson Mandela while he was in prison. Woolworths drew on this shared musical experience in what was meant to be part of its Operation Smile Christmas Campaign, but changed into a tribute to Madiba after his passing. This provoked deep-rooted memories and emotions, and further entrenched a connection between consumers and the Woolworths brand. This article was published on Marklives

Red is the warmth of the sun on your skin. It is the sweet taste of strawberries and perfumed scent of roses on Valentine’s Day. It is spicy food that numbs your tongue. It is the bitterness of hate and anger. Red is passion. It is the feeling of love and heartache. Red is strength and power and energy. It is dangerous and threatening. It is dancing with the lady in red. It is standing too close to the fire. It is the blood of war. It is the crunch of autumn leaves and waking up on Christmas day. Red is loud. It is the nostalgia evoked by drinking a cold glass of Coca Cola, eating Kellogg’s cereal for breakfast like you used to as a kid, and sharing a bucket of KFC with friends. It is riding in the trusted family Toyota, and watching the news on CNN. Red is familiar, bold, and loyal. These are just some of the ways that multisensorial marketers could describe something without actually referring directly to what it looks like. They are able to describe something innately visual through the use of the other senses: what it feels, tastes, smells, and sounds like. “Meet South Africa” (a tourism brand) immerses the viewer in the world of South African sensory experiences — the feeling of sand between your toes, salty ocean air on your face, the rush of surfing, and the intricate detail of textured art; the rhythmic sound of drum and dance and language; the earthy aroma and taste of wine and fruit. This is a multisensorial experience of SA that doesn’t depend solely on sight. Things Unseen This is not to say that the visual is unimportant. The use of colours and symbols in marketing establishes an affiliation with, and recognition of, a particular brand. It evokes particular emotions and invokes certain images. According to a colour theory, red and yellow are believed to activate hunger and encourage excitement — no wonder there are so many food chains that incorporate those colours into their branding or outlet design. Similarly so, we are able to recognise a brand purely by looking at the outline or silhouette of their familiar logos. Some brands make use of the Gestalt theory — the understanding that our minds are able to piece together individual parts of an image to make sense of the image as a whole. Spain’s Christmas Lottery and Leo Burnett developed a beautifully composed digital campaign in 2015. It is a short animated film that features Justino, a night-time security guard at a mannequin factory. The film tells a story through visual means — scenery, facial expressions, photographs, props, and more — with subtle music and background sounds. The lack of audio narrative leaves the story open to interpretation and the viewer looks for visual clues to piece it all together, proving that sometimes the most powerful messages are those that we have to uncover ourselves. Colour-blind Shortly after the dust settled around a debate about the colour of a particular dress (which the South African Salvation Army incorporated into a message about the issue of abuse), Coca-Cola launched a teaser campaign for Coca-Cola Life. The dress debate revealed the differences in how people perceive things. This, along with a general advertising trend of social inclusion, encouraged Coca-Cola in Denmark to develop an Ishihara image (a type of image used to test colour-blindness) with a hidden message in it. Only 5% of the population could read the word LIFE amid the green and brown blobs. The campaign was well-received as it encouraged audience engagement by appealing to their curiosity. “Our idea is based on the premise of engaging many by targeting the few.” As marketers, we’re often too quick to resort to simple visual representations, rather than enriching our descriptions with other sensory depictions. The challenge is to balance the visual with other senses in order to tell a more holistic story. This article was published on Marklives

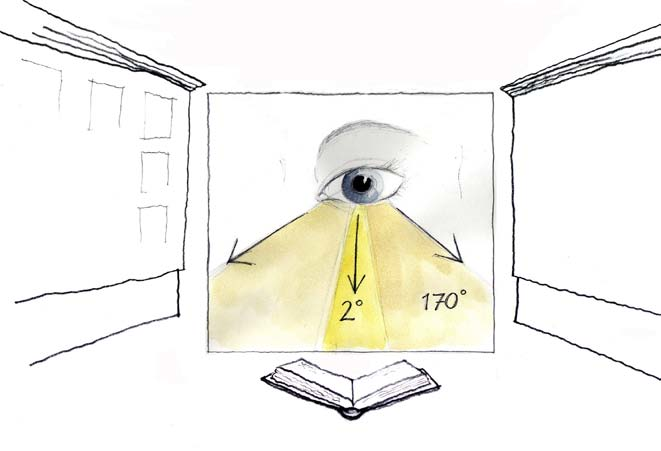

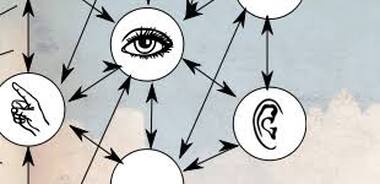

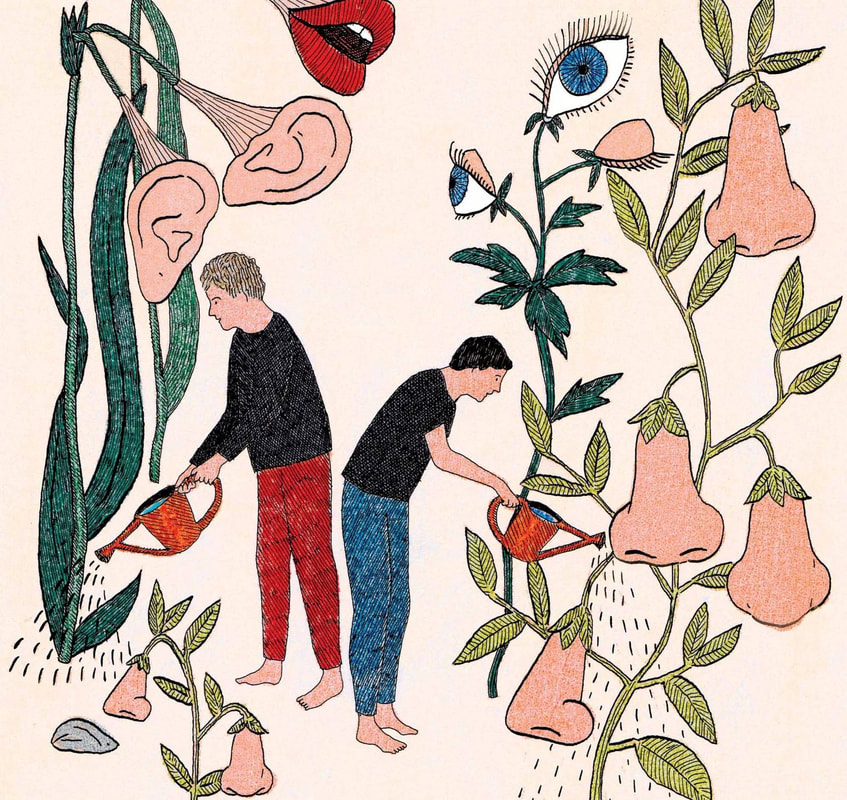

We as marketers need to take consumers’ senses into consideration if we hope to communicate effectively. But how are products that require particular senses marketed? When the channel is limited to sight and sound, as so many are, how do we represent the absent senses? Absent presence in multisensorial marketing is the technique of representing absent senses in the campaigns we develop. The challenge we are faced with is to use the senses in creative ways; to change the way we communicate and interpret meaning; and to transform the consumer experience. Humans are multisensorial beings. Some might argue that our sense are severely limited in many ways, but none would disagree that it is through our senses (and there are more than the five of sight, sound, touch, taste and smell which are usually taught to us in school) that we experience, interpret and express our world — it is how we interact with others and invest meanings in our actions. Making sense of the senses Our senses connect our external and internal worlds; they mediate our understanding and moderate our experiences. We decode meaning through our network of connections. These interpretations are influenced by our pre-existing knowledge, memories, preferences, assumptions, and experiences. The role of the marketer and advertiser is to assist the consumer in making meaningful connections and associations. For example, Hennessy’s Odyssey XO short film takes the viewer on a journey through the product’s different flavour notes (called chapters here). Taste is communicated in a complex and layered audio-visual way to immerse the consumer in a multisensorial world. Sensing the unseen An absent presence is when the original object is absent, but something else is present in its place. When a product that requires taste or scent or touch is absent, we can reconstruct the experience of it through sight and sound. The marketer’s role is to mould the consumer’s interpretation and experience of what is being represented in creative ways. Consider the Checkers’ Champion Boerewors campaign as an example. It sells the sizzle — both through the sound of boerewors on the braai, and in the repetition of the word ‘sizzle’ in a song. This activates specific taste and scent associations, drawing on the consumer’s existing knowledge and experience of a braai. Transcending the senses Marketing establishes a connection or communication between the external (a brand, a product, a service) and the internal (the consumer; their needs, desires, and sensory perception). It is no longer enough for us to market or advertise in one way — we need to make use of different senses to promote an absent product. Consumers are increasingly looking for more holistic, innovative, and immersive experiences. Cue the Netflix Switch — it dims the lights, silences calls, orders takeaways, and turns on your shows. It is a bigger experience than just viewing; it incorporates the sense of touch. It transforms the concept of ‘Netflix and chill’ into a reality. This article was published on Marklives

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed