|

In order to understand consumer behaviour on a deep and meaningful level, it requires an exploration of the underlying macro-sociological drivers (external forces) and the micro-psychological needs (internal motivators) — and an understanding of what makes us human. Similar to the ‘nature vs nurture’ debate, we could argue that there are two overarching driving forces: the human condition (nature) and cultural conditioning (nurture). What makes us human In my view, the human condition is a set of truths that is applicable to all of humanity, regardless of person, place or time. It is the foundation of what makes us human — what connects us. Theorists the world over have generally identified the ‘essentials of human existence’ as: birth, growth, emotion, aspiration, conflict, and death. We all experience these phenomena, in different ways and to varying degrees. We generally assess if our environment and experiences are dangerous or safe, and then respond to it in the ways that we have been ‘conditioned’ to. I don’t mean conditioning here in the way that Pavlov conditioned his dogs to expect food when a bell rang, but rather ‘conditioning’ in the way that culture socialises us, teaches us socially acceptable behaviour, and helps us navigate the world. What drives us Common needs drive human behaviour. This goes beyond Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (self-actualisation, esteem, belonging, safety, and physiological needs). Psychologist Marshall Rosenberg developed a list of around 30 universal human needs, such as: survival, security, freedom, connection, meaning, and more. We often draw on these needs as inspiration for brand truths, roles and purpose. One such example is when South African beer, Castle Lager, created a “share a Castle, make a friend” campaign. The concept has its origin in the idea of friendship, the human need for connection. In the human condition — the quest for survival — friendship (community, allies, bonding) is one of the ways in which we survive. At the same time, we have tensions that try and pull friends apart: money, differing values and priorities, political disposition, cultural background, and more. Castle Lager encouraged people to find the similarities within one another — to connect on a human level. This article was published on Marklives

0 Comments

Culture is broadly defined as ‘learned behaviour’. It is the language we speak, the values we uphold, the way we dress, the experiences we have, and so much more. Culture is also a context, a world in which messages are communicated. We can decode these meanings if we first understand the context. “Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning” — Clifford Geertz & Max Weber Level one: the symbols When we try to make sense of something that we see, we first do so by drawing on our existing knowledge. We compare it to what we know; we try to understand it in the framework of our own experiences, memories, thoughts. What comes to mind when you think of the colours red, white and blue? An American flag perhaps? What does this flag represent or mean to you? Do you think of the promise of freedom, devastation of war, 4th of July celebrations, the country on a map? Level two: the context Context shapes meaning. It impacts how we communicate and how we decode meanings from symbols. Someone in America looking at an image of the American flag would interpret it differently from someone in other parts of the world. For someone in America, it might be a symbol of pride, a feeling of home, a sense of familiarity. For someone elsewhere in the world, it might represent ‘the west’, entertainment, the American dream, politics. What would be associated with the flag for an American in the 1950s vs an American youth of today? Our context — our experiences, views, cultural make-up — shapes meaning. Castle Milk Stout, a South African beer associated with discernment and savouring tradition, recently released a powerful communication, driven by a movement: #GetItBack. What do you suppose red, white and blue represent in the context of Africa? Level three: the meaning The Marvel film, Black Panther, is regarded a significant milestone — not just in the entertainment world but in our lives. Addressing issues of identity, representation, development and politics, the film paints a different kind of picture of an African country. What comes to mind when you think of Africa? The answer would vary vastly if you live in Africa, have first-hand experience of Africa, or if you’ve only experienced it vicariously through images, news, music, stories, and other media. Black Panther imagines an African country neither colonised nor influenced by the rest of the world. It communicates this not only in the plot, the dialogue, the characters — it incorporates specific symbols, for specific reasons. Did you notice the BaSotho blankets? The Zulu shields and iklwa? The ritual scarification of Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda? Did you notice that the women warriors wore clothing similar to that of the Kenyan Maasai? Did you know that for the Maasai red represents bravery, ferocity and unity? Our context (our environment) along with our minds (our knowledge) shape meaning. It is when these two connect and inform one another that we can truly make sense of the symbols that we see. This article was published on Marklives

When we try to make sense of signs and symbols, there is an interplay between our outer world (our environment and cultural context that we live in) and our inner world (our mental ability to make sense of what we see, based on our existing knowledge). When it comes to advertising, packaging design and marketing-related practices, it is important to keep in mind how consumers might decipher the codes that we put out there. We need to consider the context in which people operate, and the meaning or value they place on particular signs and symbols. Hidden message Take, for example, the symbol of the bull in South Africa. The local Bull Brand — a corned meat product — draws on particular qualities of the bull in its slogan “strong like a bull”. Semiotically, the bull is both a sacred and profane metaphor symbolising wealth and social value in cultural practices (such as lobola negotiations), as well as a spiritual link between humans and ancestors. We also see the bull appearing as a character in folklore, and it has even inspired songs and dance movements (some Zulu dancers have imitated mannerisms of the bull to signify their strength, courage and dignity). The colours we see in the branding and packaging also have certain significance. Depending on the context, the colour red has many meanings that range from violence to passion, from sacrifice to good fortune. If we look at Red Bull — an Austrian energy drink — the bulls are said to depict strength, while the colour red is interpreted as power, aggression and risk-taking behaviour. Clear meaning Cape Town-based gourmet coffee bar, Rosetta Roastery, has pioneered a creatively informative packaging design to help consumers learn about and understand the different characters of its coffee. The design features an overlay of shapes — circle, square and triangle — and colours to represent origin and taste experience. Its name comes from the Rosetta stone, said to be the first ancient Egyptian bilingual text recovered in modern times that could assist in translating hieroglyphics. Another example of inspiration drawn from the stone is the Rosetta Stone language programme that applies learning methods with speech recognition technology. By drawing on existing symbols that already convey particular meanings, these brands are able to enhance the associations consumers make. Finding value The technique of applying semiotics to meaning-making goes beyond our world of marketing and advertising. We see signs appearing in the world around us on a daily basis, often without us even noticing that we are decoding them. Musicians might communicate their status or wealth in music videos by surrounding themselves with expensive cars and flashy friends. We are able to instantaneously identify these symbols of access without giving it much thought. In a recently popular and thought-provoking, tear-jerking TV series, This Is Us, there are scenes in which no words are needed to tell a story. Even if you’ve not watched the show, you would be able to decipher — to an extent — the scene below. A full understanding of the story requires context. Through the visuals, tone, and emotions that it evokes, we can piece together a story about two young people meeting (one a poet), falling in love, falling prey to drugs, losing themselves, creating life (a baby), and the mother losing her own. Take note of how the weather changes from sunny to stormy to mimic their inner turmoil, how the music is hopeful yet sombre, and how the poet’s handwriting changes to indicate a change in circumstance and character. We use signs and symbols for different purposes: to help consumers navigate products, to code specific messages into our brands, or to conjure up particular meanings associated with the images. It is important for us to anticipate how consumers might decode these signs, in order to communicate clearly, relevantly, and effectively. This article was published on Marklives

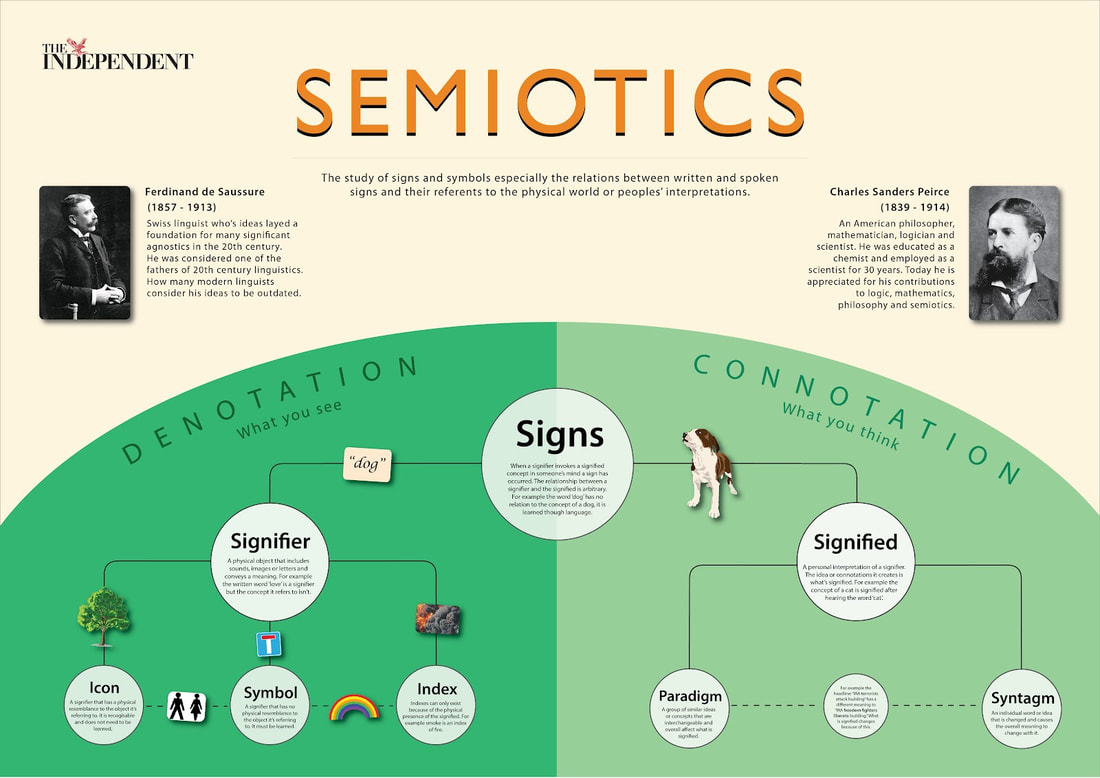

By definition, semiotics is the analysis of sign systems, and semiology is a scientific study of the life of signs within society. These signs may only be understood and made meaningful in a cultural context.The study and theory of signs is built on the foundation of linguistics, philosophy, psychology, and anthropology – as well as paradigms such as structuralism (understanding human culture and behaviour within a broader system) and post-structuralism (a critique of structuralism, and a placement of the human being at the centre of knowledge production). Hypotheses, challenges and semiotic models Academics have long studied the hypotheses, challenges and semiotic models of Ferdinand de Saussure (a French philosopher and linguist responsible for inventing the two-sided sign – composed of the signifier/material object and the signified/mental concept), Charles Sanders Peirce (a philosopher and scientist who believed that one sign could trigger a chain of associations), Roland Barthes (a semiotician best known for his exploration of cultural myths and values, and analysis of semiotics within the frame of feeling, fact and imagination), Michel Foucault (a social theorist of knowledge, power and control),and Claude Levi-Strauss (an anthropologist concerned with the highly complex and patterned nature of the human mind), among so many others. Since the early 1990s, anthropologists and psychologists have explored the consumer mind beyond the results offered by quantitative surveys or qualitative focus groups. By the late ’90s, they had developed a deep understanding of experience, influence, perception, reaction, emergent language and imagery, cultural context and change, and future opportunities and thinking (read Semiovox: Why Use Semiotics). The semiotics used by researchers, analysts, consultants, and creatives today is a combination of consumer mindset (perspective, understanding, and interpretation), motivation (their expectations, experiences, and subconscious drivers), and underlying cultural codes (meanings derived from their sociocultural context), as identified by Mark Batey. In a commercial context, semiotics is used to identify, anticipate and shape trends, to understand consumer behaviour, and to communicate effectively, relevantly, and accurately to consumers.

Cultural meaning Semioticians have the ability to distil complex meaning-making systems and culturally coded symbols into impactful insight, to translate their findings into actionable solutions, and to influence client perception and consumer decision (read Chris Arning: 10 Myths of Semiotics). Their work is increasingly being used in brand identity and positioning, communications, product development, packaging design, consumer segmentation, portfolio management, market development, innovative thinking, developing ideas, and more. The value of a brand is found in cultural meaning. And semiotics is the key that unlocks this. This article was published on Marklives

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed