|

People are cultural beings. Everything we do is cultural — our behaviour, language, relationships. Material culture forms part of our cultural make up — it constitutes part of our physical world. Some even argue that “there is no single type of human activity without its material accessories”. So, what would a tangible material culture look like in an intangible world, then? Imagined In theory, materiality refers to objects that are created, exchanged, and consumed. Material culture explores behaviours, rituals, and norms around these objects. Anthropologically, researchers are concerned with the production, history, value, and meaning of material objects. Philosophically, there are theories around the relationship between objects, and between people and things. Computer-generated imagery (CGI), augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) have been around for a while but have more recently found their way into advertising. On the one hand, this often raises questions surrounding the ethical use of computer-generated celebrities (who have long passed) to star in commercials, such as the Galaxy chocolate ad that features a digitally created Audrey Hepburn. AR, on the other hand, juxtaposes real life with CGI to alter the way the viewer sees the world (through a technological lens). Here are 15 impressive adverts that employ AR to communicate an impactful message or experience. It’s been argued that digital is either the death or future of advertising, depending on how you view it or how you make use of technological advancements. Invented We are creating new material culture through technological innovations and social networks — merging digital with cultural. The digital era and increasingly globalised world we find ourselves in has given rise to a new kind of material culture. We have terms and laws for intellectual and cultural property — for intangible property. We are able to connect with others and make transactions or exchanges across time and space — in cyberspace. We are able to create alternate realities — virtual and augmented realities. This is the future of consumption and advertising. The trick to this is not to keep up with social trends (like McDonalds) or falsely mirror them (like Disney) but to invent and anticipate them (like Amazon). Social scientists have long observed social changes and changing societies to understand how these systems and structures operate, and where they are headed. Two such examples are the McDonaldisation and Disneyfication of society. The former is a theory of a homogenised and hybridised society in which fast-food principles dominate: efficiency (completing a task in minimal time), calculability (a quantifiable objective or outcome, not a subjective one), predictability (routine and repetition create similar service delivery), and control (replacing people with technology). Disneyfication is the process of removing a place or event of its original character and replacing it with something watered down and unrealistically positive. We have more recently experienced the Amazonisation of everything — creating a customer-led and customer-focused culture by merging technological innovations with customer experience. Tangible For further reading on material culture, and why things matter, anthropologist Daniel Miller explores this topic in depth, particularly: virtualism (claiming to reveal reality but actually masking it), semiotics (the relationship between levels of representation), and relative materiality (the assumption that objects represent people). These topics are important to consider as we venture further into a technological, digital, and consumer-centric era. This article was published on Marklives

0 Comments

Material culture is the relationship between material systems and the human being. It is the intersection of learned behaviour and instinctual interactions with objects. In other words, it is how we produce, exchange or consume a material object; whether those methods are born into our instincts (nature), or we are taught through socialisation (nurture). Personified Material culture is the physical aspect of culture. It is the relationship between people and things. An object has physical properties — the materials it is made up of, and the cost of the production that went into making it — but it also has semiotic and intangible value, meaning and qualities. Have you ever wondered how packaging is designed? Why a tap opens when turned to the left? Why a soda bottle is indented at the middle? Or why a computer mouse is curved? The design is inspired by ergonomics — the process of designing products to fit the people that use them; it is about comfort and function. Coca-Cola applies this “human tech” way of thinking when creating new pack designs, as well as taking into consideration how to make the most-efficient use of its employees’ time. It prioritises the human factor in the interaction with products. Objectified Material culture blurs boundaries. We are able to trade commodities across time and space: transporting goods to/from far-away places, or passing on and receiving heirlooms across generations. Objects have the ability to blur these spatiotemporal boundaries. But material culture also defines barriers. It’s able to take the abstract or imagined aspects of a person — their personal identity, social status, religious belief — and make them tangible. Objects categorise people. Take, for example, what we wear. Our clothing is a representation of how we see ourselves and how we want to present ourselves to others. It both expresses our individual identity, and it gives an indication of the broader sociocultural context we operate in. How we dress is influenced by who and where we are, both in space and time. We’ve all seen the recent H&M advert depicting a person of colour wearing an item of clothing that caused much unrest. In order to understand how this material item manifested itself into discussions of oppression, racism and social conflict, it’s important to consider the different elements of this object.

The advert was subject to controversy and public outcry because of what the object represented — historically, socially, personally. Materialised It’s vitally important for marketers, advertisers and brands to take note of all elements of a product:

We need to understand the learned and instinctive behaviour around the use and consumption of products, the trading patterns and commercial channels through which products travel, and the semiotic context the products operate in. This article was published on Marklives

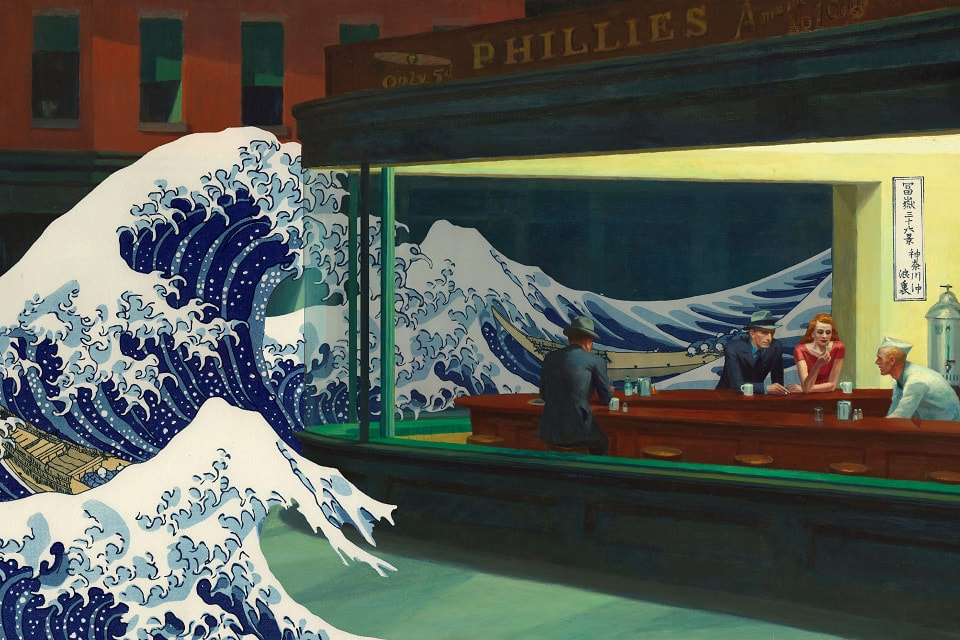

What happens when material culture items are removed from their original context — as we see more and more brands drawing inspiration from various cultural sources — and transplanted into another? If such an item is the source of interaction in one setting, what does it become in another? That all depends on the distinction between appropriation and appreciation. Culture is defined as ‘learned behaviour’ — it is how we dress, what we eat, the things we believe in, how we interact with others, the practices we participate in. Everything we do is cultural; it is learned. Material culture is our learned behaviour around and interactions with objects, products and brands. Material culture is the tangible translation and evidence of a community’s heritage, identity, behaviours, beliefs, and more. Appropriation The problem with appropriation (the misguided adoption of elements of one culture by another) is that it disregards the origin, complexities and cultural value of the items or elements that they then claim as their own. Fashion brands tend to be the key perpetrators in cultural appropriation, where they either draw inspiration from patterns, symbols, hairstyles or accessories, or simply copy and paste entire elements. Examples include Gucci’s Geisha-themed 2017 autumn runway, Chanel’s Bantu knot featured in its 2017 campaign and Victoria Secret’s Native American-inspired runway piece, all sported by predominantly white models. What makes this offensive — apart from it being seen as a modern form of colonial behaviour, where one dominant cultural grouping takes advantage of another — is that the dominant group picks and chooses aspects of a minority group that it finds appealing, removes the cultural value attached to it, and makes it purely about image, status and aesthetics. It transforms something complex and dynamic into something static and flat. Appreciation In understanding material culture, we are more likely to gain insight into the ways in which people express themselves and who they imagine themselves to be. If appropriation is on one end of the spectrum, appreciation is on the other. It’s not to say that we should avoid all contact with or inspiration from some form of cultural expression that’s not our own. We can appreciate something without appropriating it. Designers, artists, marketers, advertisers can collaborate, exchange and celebrate through their interactions with people. It is about sharing the value and expressing the significance to an audience while doing justice to the source of inspiration and the people from which it originates. For example, Quartz published a video telling the story of how designer Osklen participated in a mutual exchange between himself and a community in the Amazon when creating his spring collection. He was in awe of the details of their designs and forms of expression and, in return, the community received royalties and recognition for the role it played in the design process. This article was published on Marklives

Material culture is an area of research that explores the relationship between consumer and product — the processes involved in the production, consumption and interpretation of objects. It’s an understanding of the material side of human culture, and a belief that materiality is a form of cultural expression. This series of columns, Why Things Matter, applies an anthropological lens to the world of commercials and commodities. Branded An object has two types of value attached to it: material value and sentimental value. The first is often a monetary amount, derived from the quality and cost of materials used and labour invested in the production of the product. The second is the imagined or subjective value associated with an object based on what it means to or evokes for the consumer; it is often prompted by a brand as a marker of status, identity, or other evaluative criteria. Both forms of value allow us to perceive an object with meaning, to see the object as a reflection, a representation and an indicator of who we are. Humanity has the ability to create and transform the material world and, in return, we are shaped by it. Brands — more so today than ever before — have become a driving force behind an attempt to make a change, to have the world reflect the vision of what people believe it should be. We see brands championing causes, taking a stand, making their voices heard. We expect brands to behave in a way that is in line with and relevant to the sentimental value we attach to them. Just as we expect to get what we pay for — to have the monetary value translate into quality, craftsmanship, and care. A brand is a symbol of just as much our own identity as it is of the brand’s identity itself. If Nike says you can do it, you expect its product to help you achieve the seemingly impossible, and to present you to others as someone who is driven to succeed. A timeless tagline from 1948, De Beer’s statement that “a diamond is forever”, creates the expectation that a diamond — like the relationship with the person to whom you gifted or from whom you received a diamond — will last forever. A brand is a marker of value and, when an object is successfully branded, we perceive it to matter more. To illustrate the point, below are two instances of where brands either succeeded or failed in growing their perceived value. Successful branding Many brands have championed campaigns for the empowerment of women, but few have spoken up about #FreedomForGirls. The reality for many girls the world over is one plagued with violence and control. Considering International Day of the Girl, The Global Goals has released a video to encourage people to make their voices heard and take a stand for freedom, choice and access to opportunity for girls. Concurrently, Facebook created a profile picture frame to celebrate “today’s girls, tomorrow’s leaders”; an empowering message that steps away from cultural notions of weakness commonly associated with girls, and toward one of admiration for what girls overcome and what they are capable of. Usually when a brand stands for something, its communications often paint a bleak and hopeless picture hoping to evoke sympathy and empathy. In doing so, they perpetuate reality that the ‘something’ they stand for is weak and in need of help. The examples above take a different approach. They portray girls as powerful individuals in their own right and are great examples of how brands can not only shape perception, but alter reality. Brand fail From the start, Dove’s Real Beauty campaign was an attempt to engage with critiques of whiteness in advertising, as well as challenge unrealistic and digitally enhanced female bodies. This is what made it so shocking that a brand claiming to be ‘committed to representing the beauty of diversity’ — and apparently targeting an audience who would recognise feminist codes, an audience well-informed, and able to afford its products — would sign off on an advert that showed a woman of colour removing her clothing to reveal a white woman. Rather than addressing issues of cultural conflict, racial tension, and gender misconception, Dove have added fuel to the fire. This article was published on Marklives

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed