Stand your ground With the world largely being homebound since March of this year, many have been using this as an opportunity to change their space. It is, of course, the privileged who are safe at home (not stuck at home or scared at home) and equipped to develop their homes to meet their evolving needs. Ikea, regarded as the “go-to store for the masses with empty rooms to fill and life-stages to adapt to”, was expected to profit from this trend but, instead, suffered as it temporarily closed stores and failed to adapt to ecommerce practices. However, it’s said to be taking a ‘post-pandemic gamble’ and will be opening 50 new stores in cities (particularly in the UK). What makes this surprising is that: 1) online shopping — not in-store visits — is booming, and 2) people have migrated away from cities to the suburbs, the country, and to the coast. In addition to this, Ikea stores across the UK will be hosting an initiative in which customers can sell their used furniture back to Ikea for up to 50% of the original price. The intention is to “help customers take a stand against excessive consumption”.

This article was published on Marklives

0 Comments

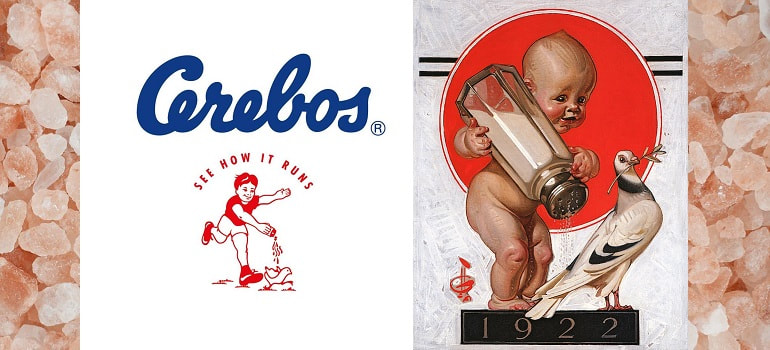

Who’d have thought, at the start of this new year and decade, that there’d be a resurgence of past political movements, socially fuelled structural violence, a health pandemic of crippling proportions and economic collapse? History rhymes I had a little bird Who could have known, when we shouted “Happy New Year!” as 2019 transitioned into 2020, what would be in store for us? Experts claimed we’d had a prosperous decade, far more fair and fruitful than 30 years ago (listen to Steven Pinker here), and populations the world over anticipated a return to 1920s fashion, music, and art. The Roaring Twenties were considered a ‘Golden Age’ because of the economic boom that followed the end of World War I and the Spanish flu. These factors, among others, contributed to a global socio-political paradigm shift. Were we crazy to anticipate a positive trajectory for the 2020s? Were we foolish to think we could get the gains without the pain? In 1921, German-born American artist, JC Leyendecker, created an illustration for the Saturday Evening Post’s New Year’s Eve edition (for 1922). It was one of a series that spanned 40 years but what makes this one particularly interesting today is its relevance 100 years later. It depicts Baby New Year throwing salt on the dove of peace. In various contexts, the dove symbolises innocence, renewal of life, the end of war, deliverance, forgiveness, and peace. But why the salt? To prevent the dove of peace from flying away, of course! Salting a bird's tail He went to catch a dicky bird, There’s a nursery rhyme that dates back to at least the 17th century. This, in turn, is believed to be derived from a folktale that states you can catch a bird by putting salt on its tail. The reason for this is: a) the salt startles the bird, b) the salt interferes with the bird’s ability to fly away, c) there are magical properties in salt that cast a spell over the bird, or d) if you’re close enough to pour salt on a bird’s tail, you’re probably close enough to catch it anyway. On a metaphorical level, salting a bird’s tale is an analogy or idiom for immobilising people. South African audiences would be familiar with the iconic local salt brand, Cerebos, and its illustration of a child chasing a chicken, trying to pour salt on it. While the slogan “see how it runs” would seem to refer to the chicken running away, it in fact refers to the chemist who mixed calcium phosphate with salt, giving it free-flowing properties. It’s the salt that runs. What Epidemiologists and medical anthropologists would be familiar with the term “syndemic”. By definition, it’s the result of multiple epidemics or disease clusters. It’s the interaction of these diseases and the contributing factors (particularly social, environmental, and economic) and conditions (namely poverty, stress, and structural violence) that worsen the burden of disease. A typical biomedical approach would isolate a disease or pandemic, and then study and treat it as a distinct entity — not connected to anything and independent of context. A systemic approach explores a phenomenon in context and in relation to surrounding phenomena.

This article was published on Marklives

South Africa’s story is one suspended in turbulence and this notion of uncertainty has rung true for decades. It’s not surprising, then, that Springbok Radio back in the day hosted a competition that asked listeners to decode the acronym: EGBOK. Just as the springbok transitioned from a symbol of separation to hope and then to unity, so, too, can we shift our national narrative and know that Everything’s Gonna Be OK. THENThe 1950s was a post-war era most commonly associated with a time of conformity and ‘traditional’ gender roles. Pop culture and mass media echoed messages of an ‘ideal’ society that largely excluded people of colour and fetishised domesticated women. It was during the Cold War that the term “nuclear family” was introduced to encourage American women to refuse a career and maintain their family instead. The US was introduced to commercial television, with a growing interest in and supply of soap operas. The target audience of these dramas, which were predominantly sponsored and produced by soap manufacturers, was assumed to be the typical housewife cleaning the house while she listened to the radio. Meanwhile, South Africa launched its first commercial radio station: Springbok Radio. Similar to US TV at the time, its programmes were reminiscent of white suburban life. By the 1970s, it was making impressive strides (both financially and in listener popularity) yet, by 1985, Springbok Radio was operating at a loss and so it closed. It’s often stated — with undertones of shame — that South Africa was one of the last countries in the world to get a regular TV service (which happened in 1976). Those in leadership positions prior to 1976 opposed its introduction as it was feared it would bypass parental control in the household and encourage behaviour not accepted by the state. Despite the late shift to TV, the impact of listeners transforming into viewers meant that less time was spent listening to the radio, and more spent on watching TV. This ultimately led to the end of Springbok Radio. Goodbye to The Adventures of Jet Jungle, sponsored by Jungle Oats and Black Cat; to the BP Smurf Show; and the Chappies Chipmunk Club. No More General Motors on Safari or the Castle Lager Key Game. Not one more Guess Who with All Gold or greeting the bride with Nestlé. NOW For some South African youth, 1985 was the end of their childhood memories; of gathering around the radio to listen to stories, music, sitcoms, news, and chat shows. For all of SA, 1985 signalled the beginning of a crumbling oppressive system. The nation collectively held its breath and wondered what the outcome would be. Following Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 and the official political dismantling of apartheid, SA was allowed to participate in the 1995 Rugby World Cup — and won. Up until then, rugby and the Springbok team had been perceived as a symbol of division. As SA chased its dream of being a rainbow nation, the Springboks’ win transformed rugby into a symbol of hope. In 2018, Siya Kolisi became the first black captain of the Springboks — born a year after Mandela was freed from prison but still carrying the weight of apartheid — and a year later he led his team to victory in the 2019 Rugby World Cup and rugby has become a symbol of unity.

This article was published on Marklives

The morning of the first day of lockdown, I was woken by a complete absence of sound. It felt like a scene from a budget sci-fi film. The usual rumbling of a delivery truck outside our window wasn’t there. The call and response of people either side of the street was absent. The incessant hooting of taxis was gone. Even the overly vocal dog next door was silenced. Only the wind, like the hum of a distant ocean, found its way through a gap in the window frame. A dove swooped past and I felt and heard it, rather than catching a glimpse. Soundscapes & fearscapes — sounds of life Our acoustic environment is filled with soundmarks that make our immediate soundscape unique, compared to anywhere else in the world. These sonic facets of a community offer insight into the physical qualities of and social actors within a space. Similarly, stories and storytelling help us make sense of our surroundings, as well as how we imagine a future world and the people in it. Storytellers have the power to create a sense of fear or of hope in relation to future possibilities, as well as a notion of optimism or pessimism towards humanity and its ways of being. Cyberpunk & Afropunk — narratives of revolution & resistance On a Saturday in April 2020, a community of futurists and authors gathered virtually for a nine-hour symposium: Science Fiction as Foresight. Writer Karl Schroeder presented on theories of change, identifying six lenses through which we perceive change. Paraphrasing his definitions:

Conducting fieldwork in a pandemic isn’t only possible but necessary. Brands and businesses have the opportunity to be present and listen. Here are some innovative ways that researchers are exploring the world while staying home: This article was published on Marklives

Each generation is born into a different time, with its own set of challenges, opportunities, and shared experiences. This temporal consideration — among many other factors — plays a role in how someone might respond to a crisis. A global generational war is brewing over the novel coronavirus. Or so it seems. Some preach the severity of the situation (often older people), while others continue with life as usual (many younger people). There are even those who act in purposeful defiance, like attending corona parties. Where is the difference in reaction coming from? It boils down to three elements that are playing out in different ways: physical distancing, cognitive dissonance, and social solidarity. Myopia: A forgotten past On the phone with my grandmother, before South Africa officially went into a three-week lockdown, she told me to ensure I have the following: 1. Food 2. A radio 3. Puzzles My grandmother was born in a small Karoo town in 1931, and so was raised during the Great Depression and World War II. She’d lived through scarcity, uncertainty, and boredom. Her advice for covid-19 supplies spoke to the need for sustenance (food), information (radio), and entertainment (puzzles). She’d lived through this scenario before, and has been able to adapt. However, many aren’t, whether it’s not having a similar frame of reference against which they can make judgments, or not wanting to return to a state of limitation, or not being afforded the privilege of making drastic changes to their current lifestyle, or even simply not wanting to give up their freedom of choice. We need to understand change from multiple perspectives, and not make assumptions. In times like these, brands and businesses need to consider multiple possibilities and prepare several solutions to meet the population’s new and varied needs. Dystopia: An apocalyptic reality Sohail Inayatullah’s framework for thinking about the future is useful in understanding where we are right now, and where we need to be to make it through a crisis. The framework is divided into six foundational concepts:

Utopia: An imaginary future Oscar Wilde considered progress to be the realisation of utopias. Many literary and philosophical theorists believe that a utopia is more revealing of the time in which it was formulated than of what people actually imagine would occur in the future. If, today, people dream of a future where there’s an abundance of natural resources and an elimination of inequality, this is a reflection of our present reality where we experience shortage and disparity. What could South Africa’s utopia look like?

This article was published on Marklives

Play. It’s something we associate with childhood, somewhat carefree and careless. However, there’s more to it. Games usually have rules and rituals attached to them which make them far more complex than mere child’s play. Games are reflective of both the players and of the times in which they are played. Social life is reflected in play.

A successful crossword puzzle is ‘creative, clever, and current’. It is about exercising your brain, escaping from daily responsibilities, and passing the time. Ford, intentionally or not, recognised the value of connecting with consumers through something that mattered to them: leisure time. The multinational brand had been part of South Africa’s motor industry since 1923 — 10 years after the crossword was introduced. In the late 1950s, a local newspaper printed a crossword puzzle. The sponsored prize was a Ford Consol. My grandfather filled in the puzzle and, when he reached the final clue, he thought he would write a humorous answer to make my grandmother smile. What was it? “Mary would be really sad to lose this: L _ M B”. The answer he wrote? “LIMB”. He won the car.

This article was published on Marklives

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed