|

What is “cancel culture”? As an anthropologist, anything relating to culture intrigues me. Although, arguably, everything humans do is cultural, and all culture is human culture. In black and white Cancel culture caught my attention because it wasn’t something I fully understood. From the outside looking in, it seems to be a form of ostracism and public shaming: silencing someone or something not considered socially acceptable or agreeable. My understanding is that there’s a trigger event or trend towards a turning point that sparks outrage and visible disapproval of a public figure (a person, brand, or the like) that’s held accountable for their actions. This then leads to a number of people exerting social pressure on others in order to encourage them to withdraw their support, too. The hashtag #isoverparty has become synonymous with cancel culture. Some argue that a person should be split from their actions — an artist is separate from their art — and, therefore, support for their work shouldn’t be impacted by what they do in their personal capacity as a human being. Grey matter This brings me to the notion of “splitting”. This is a term often associated with psychological diagnoses in which individuals place people on either extreme of a spectrum; they are either idealised and idolised or devalued and shunned. Psychologists recognise that splitting is a protective mechanism that particular individuals develop in response to previous abusive, harmful or traumatic experiences. There’s so much behind call-out and cancel culture that it can’t be simplified into ‘good or bad’ categories. Social systems and human behaviours aren’t mathematical; it’s not an equation that’s categorically right or wrong. Rainbow nation Trevor Noah, comedian and The Daily Show host, has been vocal about cancel culture, calling for counselling, not cancelling, and allowing for sincere apology (coupled with an attempt to right any wrongs) to result in absolution. I’m reminded by something the late great Maya Angelou said: “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” What will you do differently today to honour and respect the dignity of others? How might you align yourself with brands, businesses, and behaviours that uphold an honourable and humane set of values and ethics? Originally published on Marklives

0 Comments

I am because we are I drive a small Suzuki Jimny. No, not the newer model that looks like a mini Mercedes G Wagon but the one that looks like a little Jeep Wrangler. I don’t know much about cars. When I made the choice to get this one, it was based on my desire to be prepared in case I ever needed to go off-roading (I don’t know when that would’ve been as I worked in the city at the time, and pavement-hopping is frowned upon). The second motivation behind my decision was that I wanted something compact: easy enough to parallel park, squeeze through narrow streets and get me (and one other person) from one point to another. What I’d not accounted for, though, was that, in driving a Jimny, you automatically become part of an unofficial community. When passing by someone else in a Jimny, it’s not unusual for them to wave, smile, flash their lights or even hoot at you. If you’re spotted in a parking lot by a fellow Jimny-lover, a conversation will be sparked as if you’d known each other prior or had more in common than just the same vehicle. Just as nothing can exist outside of meaning, so too can no one exist in isolation (read more on Bakthin’s theory of connection and interaction here). A self-love movement Anthropology has a troubled history with the distinction between “self” and “other”. In a process of “othering”, the unfamiliar and the unknown (from the perspective of the anthropologist) would be viewed in a negative light: exoticised, alienated, stereotyped, stigmatised, and even feared (read more on the topic of ‘otherness’ here). This created a contrast between what was considered to be the norm and the so-called unusual, the centre and the periphery, the majority and the minority, the familiar and the strange, the self and the other. Cue the selfie generation. This is one of the ways in which today’s youth are referred to owing to their preoccupation with themselves — their appearance, their innate worth, and their internal reflection. On the surface level, this may come across as somewhat self-absorbed but let’s dig a little deeper. The term “narcissism” is being thrown around a lot lately, not in reference to young people but to their parents. Just have a look at this “raisedbynarcissists: for the children of abusive parents” Reddit thread. Self-love is nothing new. Some even trace it back to the American Beat Generation of the 1950s and ’60s. They’ve been credited as the originators of naked self-expression — an unfiltered, vulnerable, and exposed presentation of self. The intention was to promote love, peace, and regeneration through protest and performance; to reconcile the brutality of war and the destruction of nature through consumerism. One key difference today is that the message of restoration is centred on mental health and wellbeing, and the platform on which this message is communicated is primarily social media. Entangled existence In a recent international seminar, focused on creating a community that supports one another in being “the change we want to see in the world”, one of the event hosts had a profile picture that caught my attention. It was of an illustrated figure playing what appeared to be guitar strings, only the strings were tied to the character’s mind and heart. It was accompanied by the Spanish word “afinando”, meaning fine-tuning, refining, fixing, honing. Being human is being in a constant state of adapting, adjusting and accommodating. If we think, speak and act on the basis of assumption, judgement, and bias, we’re more likely to discriminate, offend and exclude. The same goes for the opposite: if we consider our interconnectedness and interdependence, we’re more likely to exist in empathy, solidarity and commonality. What will you do differently today to see yourself in others and to exist in a shared humanity? How might you fine-tune the connections between what your mind thinks and your heart feels? This article was originally published on Marklives

Have you ever recognised something familiar embedded in something strange — a shape in the clouds or a face in the shadows? Have you ever noticed a pattern scattered through disconnected phenomena — repetition in data or similarity in scenarios? How do we know when an observation is deeply meaningful or simply coincidence? This might help explain why we see more people going with their gut, rather than sticking to science, or how some brands evoke emotional reactions from audiences while others remain distant and disconnected. (Read more on “apophenia” if this topic interests you.) Lucky number 7 I recall a professor once saying to a room full of bright-eyed anthropology students that, as human beings, we only see what we expect to see and what we expect to see is what we are conditioned to see. This stuck with me. I wondered if my reality was determined by how I perceived the world around me. Was my perspective conditioned by an inherent and innate nature, or was it conditional to nurtured experiences and circumstances? Take, for example, the number seven. It might start with me moving into house no. 7 in the street. I then notice my mom reading Lucinda Riley’s The Seven Sisters book series. I come across a theory on the science of human origin in Africa, called “The Seven Daughters of Eve”. I am reminded of the seven sins and seven virtues as I research a project relating to religious philosophy. I then see Hennessy’s Seven Worlds advert. What, if anything, is the significance of the number seven in relation to my life? Confirmation bias “Confirmation bias” is the term psychologists have long used to describe “the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs or values”. Businesses are catching on. If you search online for articles on the use of confirmation bias in market research and in advertising, you might be surprised to see what you find. For example, one is titled: “How errors in reasoning can be used in marketing”. It goes on to list five ways to ‘exploit’ this phenomenon. This could potentially be tied into another conversation regarding Gestalt theory, which designers have been incorporating into user experience (UX) and related fields: “Gestalt Principles are principles/laws of human perception that describe how humans group similar elements, recognize patterns and simplify complex images when we perceive objects.” Correlation is not causation Anthropologist Leslie White has argued that our ability to translate and transform symbols in meaningful ways is one of the key qualities that makes us human. The challenge, however, is discerning the meaningful from the meaningless. This is not to be confused with the notion often shared in research settings: “the absence of insight is an insight in itself.” Put another way: we exist in living systems that continuously change. Meaning-making occurs within this same state of existence. Just as we live and die and life continues, so too must meaning rise and fall and endure. Dave Snowden and Nora Bateson, in a recent dialogue on “when meaning loses its meaning”, explored “how meanings stretch, transform and sometimes wear out across ecosystems of communication”. What will you do differently today to look at the world differently — to make conscious decisions in some situations and to let go of control in others? Originally published on Marklives

Do you know — or remember — the Norwegian story, Three Billy Goats Gruff? It’s a cautionary tale that warns against the temptation and consequence of greed. It tells the story of three goats wanting to cross a bridge to get to greener pastures. However, a grumpy troll lives under the bridge and refuses to let them cross, threatening to eat them. The first two manage to cross over, owing to their persuasive promise of something better to come. That is, until the final goat shows up — larger than the first two — who manages to knock the troll off the bridge and into the river. To infinity and beyond “The bridge can only be crossed when we get there, not before.” —Wittgenstein A bridge is a peculiar structure. It is both a concrete structure and an abstract metaphor. Semiotically, it symbolises both division and connection: two separate spaces or entities brought together. The bridge constructs the whole but also maintains its distinct parts. According to Dinda L Gorlée, “Semiotics is regarded as a constellation of beliefs, values and techniques which serve as a unifying matrix or technique mediating knowledge” (more on semiotics here). A semiotic bridge, much like the architectural structure, is constructed. In this case, a bridge is built of signs or codes, messages and meanings that connect data or information, and support those connections. Just as semiotic bridges exist, so too do semantic barriers. These are symbolic obstacles that distort a message from its originally intended meaning, making it unclear and ambiguous. Barriers take the form of contextual factors, such as perspective, emphasis, internalised meaning, and encoded language (more on semantic barriers here). Outer Limits We often hear about the core or centre and periphery or outskirts. Tiit Remm makes an important distinction here: the periphery (a dynamic space of difference and exchange) exists as a binary to the core (the stable organisation of a system). A boundary, though, separates the internal from the external. Dr C Mariene Fiol explores the notion of organisational boundaries as imagined lines that are drawn to separate an organisation from its surrounding environment, as well as internal roles that are related yet distinct. The interplay of autonomy and interdependence is understood to be used as mechanisms of control within and between organisations. The individual and the collective can’t have too much power, apparently. Semiotic borders establish, maintain, and contain — as well as unify — semiotic spaces or semiospheres (more about semiospheres here). “Every culture (semiosphere) needs another culture to define its essence and limits,” writes Dr Ekaterina Vólkova Américo in her article, The Concept of Border in Yuri Lotman’s Semiotics. Lotman’s notion of border is useful here in understanding how it can be both a divider of spheres but also as a mechanism that brings spaces into conversation and exchange with one another. It both limits the invasion of ‘alien elements’ and translates particular elements into the language of a given semiosphere. Shedding Light The bridge, the barrier, the border, and the boundary are intriguing if considered to be catalysts of change and of culture. This is where the new and the novel emerge, where serendipity and spontaneity occur, and where differences become similarities. Where would you place, say, Eskom in this story? Would you consider it a troll, a goat, a bridge or a river? As an organisation, is it greedy or misunderstood, cunning or innovative, isolated or connected, impatient or dynamic? Most media headlines paint a picture of Eskom as a power-hungry, mischief-making dinosaur (or troll). South Africans are portrayed as the smallest goat who simply wants to get to greener pastures: reluctant to take responsibility but willing to sabotage the troll to get there. The first goat passes the buck to the second goat — the South African government. This goat uses distraction and denial to get across the bridge. When the third goat shows up (in this case, the global energy crisis), everything falls apart.

What are the layers of loss? What futures emerge after death? How are beginnings and endings entangled?

This illustrated book will change the way you view death and dying, through multiple layers of storytelling that draw on Anthropology and Futures Studies. Join the community on Patreon and see the story unfold. Listen, for a moment, to the sounds around you. What do you hear? Can you identify what’s making these sounds? How do you interpret sound — do the sounds carry any information that you can make sense of? Just as there are ways of seeing, there are ways of hearing. The semiotics of sound considers that all things audible and acoustic carry meaning and are a form of communication, encoded and decoded similar to how the visual — signs and symbols — can be interpreted in context. Sound of Silence Everyone, and everything, exists in an acoustic environment, consisting of both natural and artificial sound. Soundscapes emerge from these immersive acoustic ecologies. Experts in the science of sound have identified three sources of sound and three key elements of soundscapes. Consider the soundscapes generated in your work environment or by your brand as you read through the sources and elements. What stories are being created and carried by these sounds?

In thinking about your workspace, organisation or brand, what metaphorical song does your space create? In what key is it sung; is it upbeat or slow, melancholic or uplifting? What sound signals are being sent to ‘listeners’ and how do they interpret the messages embedded within it? What soundmarks are monumental to identifying or recognising your brand’s figurative band? Speed of SoundWhen you imagine the future, what does it sound like? What sounds do you hear? What will your brand or business sound like in the future? Futures Soundscapes is a project from Mexico City that has explored the question: What does the future sound like? In developing sound-based scenarios through shared visions of the future, and the ability of sound to conjure up these images, it demonstrated the power of sound. Beyond looking for visual signs of change, we should be listening to signals, too. Perhaps the next time you conduct market research, consider keeping listening journals, reading up on sound theories, and interpreting the nature of sounds in their natural environments. The sound inside a taxi, on a train, in a bus, taking an Uber — how do these sounds shape our sensory experiences? Sound of MusicHow Bad Is Your Spotify? This judgmental AI filters through your listening data and tells it like it is. See also How AI helps Spotify win in the music streaming world if you’re curious to know how machine learning can be harnessed to “discover and act on insights from external data and user behaviour”. This is particularly important for those of us who make data-driven decisions to enhance people’s experience online. Take, for example, the Discover Weekly feature on Spotify. According to Outside Insight, the music platform generates this personalised music list for each user through a combination of three methods: making comparisons between different people’s behavioural trends and patterns, scanning online conversations to identify ‘top terms’ and to develop ‘cultural vectors’ based on these discussions, and analysing data from audio tracks to categorise the songs themselves: “In this way, Spotify portrays itself not just as a platform for popular existing musicians, but also one that provides opportunities for the next generation of budding musicians to gain recognition.” How might you, your organisation, or your brand make personalised recommendations based on past patterns and potential preferences of your clients, customers, or consumers? What will you do differently today to break from the noise, to be heard from near and afar, to not be obscured by silence, and to listen intentionally? Originally published on Marklives

Ways of Seeing revisits a previous column, Fragments. In this new series, we’ll explore the processes of sense-making, knowledge production, and world-building in our memories, realities, and imaginaries as South Africans, inspired by the use of semiotics (the scientific study of signs, symbols, and communication systems within sociocultural contexts) in our business landscape. Semiotics is growing in popularity among brand analysts as it’s “the most appropriate tool for understanding questions surrounding brand symbolism and meaning and the multiple and layered messages that underpin this meaning,” according to Chris Arning. More and more businesses are ‘tapping into culture’ to create meaningful communication, to develop human-centred design, to position themselves competitively in shifting contexts, and to cue concepts and ideas that resonate with specific audiences. “Semiotics, the study of signs and cultural meaning, has been gaining ground in the world of commercial research.” This is the opinion of Cato Hunt and Clem McCulloch in Epic. Semiotics has long been making waves in the business world but what we see emerging is a distinctly corporate and commercial form. “Commercial Semiotics can be used to strategically answer business challenges, providing cultural context as to why ideas are in people’s minds in the first place,” writes Caroline Brierley in Illume Stories. “By deconstructing culture to determine underlying codes, [semiotics] tells us how meaning is created,” says Ashton Bridges in Kelton. “Humans make emotional decisions. Those emotions are often guided by subconscious interpretations of words and images. Semiotics can help decode those subconscious messages to sharpen messaging and branding,” notes Lesley Vos in CXL.

HIDDEN IN THE DARK. We often speak of insights as gems to be mined, nuggets to be unearthed, buried treasures to be discovered, as if researchers are miners, archeologists, or explorers, and the people and places from which we draw insight are mines, caves, or uncharted territory. In this sense, culture — learned behaviour, value systems, beliefs and worldviews — is imagined to be hidden, underlying, deep below the surface, fossilised, rather than entangled, enigmatic, and evolving. Aren’t we colonising culture by hunting, excavating, and claiming it? By flagging it, moulding it, and putting it on display? CASTING SHADOWS. Have you heard the saying, “Old sins cast long shadows”? What we do today has consequences tomorrow, and the next day, and the next. In the same breath, we’ve inherited processes and practices that came before. The ways in which we gather, collect, nurture and share insight shapes the stories that are told, the perceptions formed of people, the innovations and strategies that are made. Our thoughts, words, and actions matter. Consider, for example, what comes to mind when we think of shadows. Often shadows are associated with metaphorical darkness, mystery, and the unknown. If someone behaves in a ‘shady’ manner, we question the honesty or legitimacy behind their intentions. The shadow economy is used to refer to ‘unlawful’ activities that operate outside of the formal economy and so are beyond state control or benefit. The shadow pandemic encompasses the gender-based violence (GBV) that targets women and girls. In psychology, the shadow self is a part of the individual that they’re either unaware of or choose to suppress and not make visible or known in order to control and contain a version of themselves and their reality. In thinking about our use of insight, what assumptions, judgments, and preconceptions cast shadows on the work that we do? How might we change these narratives, perspectives, and choices? SHINE A LIGHT. Jean Paul Petitimbert, semiotician and brand analyst, distinguished between two branches of semiotics — one of French origin, and the other emerging from an Anglo‑Saxon world. He explains that, “for the French strand of semiotics, the purpose of an analysis is to dive inside signs (whatever their natures), to disassemble them, so to speak, and to take them to pieces in order to understand the internal logic at work between their different components, with a view to describing the mechanisms that produce meaning.” In this sense, a brand is built on internal logics, philosophies, systems and rules. The semiotician “bring[s] them to light” so that a marketer might maintain the brand’s identity over time and space. The English variant of commercial semiotics tends to border on trend analysis. You have probably heard of codes being described as emergent, dominant or residual. This also involves a consideration for the intention and interpretation of signs and symbols, says Petitimbert. One branch of commercial semiotics focuses on the internal, the micro, and the specific, while the other focuses on the contextual, the macro, and the external. In short, “[t]here should exist marketing research programmes proposing to use both approaches in order to get the depth and width of analysis respectively provided by each type of semiotic enquiry so that clients can make really thoroughly informed decisions.”

Originally published on Marklives.

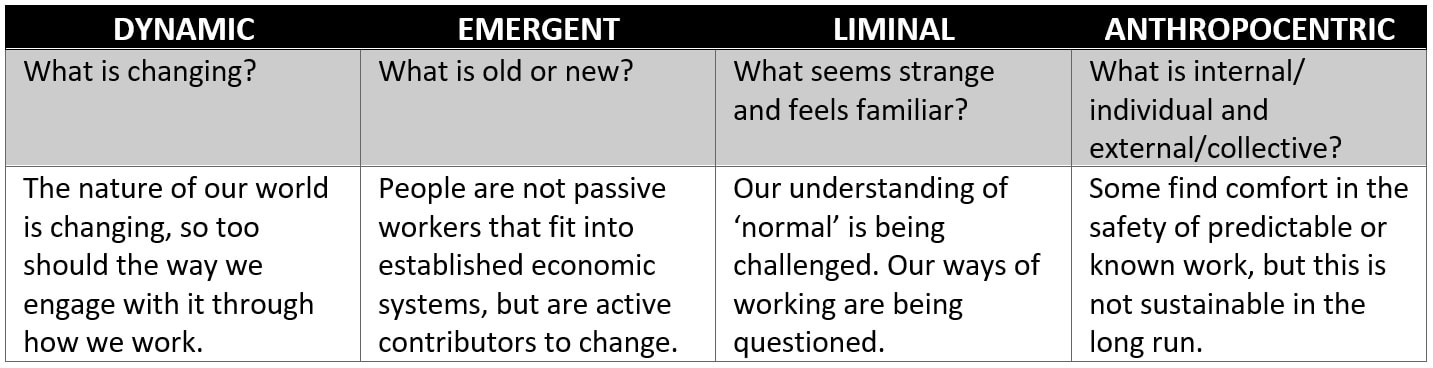

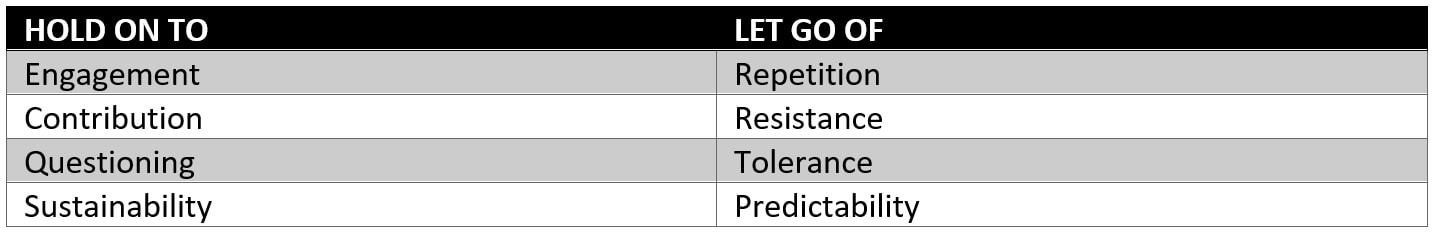

Now that I have your attention, let me tell you about fragmented truths, or fragments of truth. First, rumour. Originating from the Latin word for ‘noise’, rumour is an exchange of information whose accuracy remains unestablished (Brouksy, 2014). The content within and the behaviour around rumour sit on the fringes of fact and control; both fragile and ephemeral (Brouksy, 2014). Such information tends to arise among people who do not necessarily know each other; they are merely vehicles for the transmission of highly charged information (Stewart & Strathern, 2020). “Rumours often circulate most intensively at times of uncertainty or unrest” (Kroeger, 2017). Rumours in this sense are a reflection of particular beliefs and views about how the world works at a particular time and place (Kroeger, 2017). Historically, different narratives emerge during crises (Ali, 2020). What do the rumours of today uncover or indicate about our present? Is it a loss of confidence in established authorities (Gusterson, 2017)? How do rumours start and why do some flourish while others fizzle out? Truth in modernity is characterised by the value of personal experience and opinion over data-driven science (Ofri, 2021). Vaccine Anthropologist Heidi Larson views rumours as ecosystems that need to be rehabilitated in their entirety - not simply the pulling and removing of one thread from the interwoven network. How do we contain outbreaks of misinformation? We build trust and truth chains. Trust, says Larson, is a currency that can be created, eroded, and rebuilt. We strengthen trust by listening to the stories behind the rumours, and not falling into the trap of debunking falsehoods and fears in the face of despair. Next, gossip. Unlike rumour, gossip tends to be shared in more intimate situations or spaces and is often supported by evidence, although this is difficult to verify as it draws on biases and prejudices. Also unlike rumour, gossip is not usually rooted in past experience, but rather consists of up-to-date knowledge, an element of cleverness, and the ability to be vigilant (Monson, 2020). It requires wit, verbal skill, and dramatic flair (Barrett, 2020). Essentially, “humans like to tell stories, and gossip is an attempt to put pieces together to give shape to a story” (Stewart & Strathern, 2020). As a form of sensing and meaning-making, gossip helps us fill in the gaps in our knowledge, conjecture, speculation, and hunches (Drążkiewicz, 2020). It is a mechanism for enhancing social solidarity and a tool for advancing individual reputation or status (Besnier, 2019). Rusty Barrett (2020) traces the development of ‘tea’ as a way of referring to gossip within gay communities and amongst drag queens. Barrett looks at the different positionalities of tea: it can be poured, served, sipped, and spilled. These are all ways of engaging with gossip. Cultural norms regulate when, how and to whom it is appropriate to share particular doses of truth. The art of properly serving tea, says Barrett, requires an awareness of the most opportune moment to reveal particular information. It is the ability to transform a piece of gossip into a performance worthy of being served to a queen (Barrett, 2020). Sarah Monson (2020) explores how gossip - not as simply ‘idle talk’ - is employed by traders in Ghana’s Kumasi Central Market. In ‘using their mouths to trade’, gossip helps traders in reducing economic risk inherent in a competitive and complex environment. It also enhances their professional reputations and respectability amongst visitors, as well as their relations or partnerships with one another. Reputation is a key component of business viability (Monson, 2020). It is for this reason that “malicious gossip is feared more than complimentary gossip is desired” (Kapchan, 2020). Finally, secrets. A secret could be seen as a carefully constructed form of knowledge that is invested with value, guiding our engagements with and interpretations of truth (Manderson et al, 2015). A secret is something that is partially known in order to attract attention and create an air of importance around that which is unknown (Bigo, 2019). In other words: information is concealed in order to reveal its existence. Secrecy also has a binding and dividing effect; strengthening bonds between those ‘in the know’ and distinguishing them from those on the outside. Secrets are situated in relations; they build, sustain, and convey connection between people (Manderson et al, 2015). While secrecy may elicit suspicion, competition and exclusion, it can also foster alliance, transparency and collaboration (Coetzee, 2021). It is an intricate and intimate interplay across a range of knowing, not knowing, pretending to know, claiming to know, and feeling entitled to know (Coetzee, 2021). Some concluding thoughts. There is a theory within Cultural Anthropology that places societies on a spectrum of fear, guilt, and shame; the different ways in which social order is often established and maintained. We can draw parallels between this theory and the different forms of fragmented truth. All three - rumour, gossip, and secret - arise out of the intersection of power and truth. They are products of collective interaction with varying degrees of intention, influence and impact (Stewart & Strathern, 2020). Rumour taps into and fuels our fears, anxieties and resentments (Gusterson, 2017), gossip feeds off of our desire for recognition or inclusion and avoidance of shame associated with tarnishing or contesting our constructed reputations, while secrets speak to a sense of guilt that we often keep hidden, to ourselves, or amongst trusted alliances. As futurists, when we engage with futures - particularly the fear, guilt, and shame that might surround particular problems and possibilities - how might we use rumour, gossip, and secrets to add layers of meaning to the stories we tell, the scenarios we develop, and the situations we shape? How do we transmit ideas and make change go viral without disfiguring or exaggerating truths? This was originally written as part of a blog series for the Association of Professional Futurists What if our professional legacy is dismantle old ways of working? Creative Destruction If we have learned anything from this pandemic, it is that our sense of ‘normal’ was somewhat warped. While many long to return to ‘normal’, some say we are heading for a ‘new normal’, and others argue we should prepare for a ‘post-normal’. Just as a relationship cannot return to what is once was when a partner betrays another’s trust, or how a person’s status (and arguably their life) is forever changed once they become a parent, so too can businesses not fall back into old habits, outdated ways, or dead ideas. “We can’t blindly accept what’s presented to us as normal,” said a participant at this year’s Global Business Anthropology Summit. Although it is a difficult sell convincing a legacy team of the changes needed – not just in practice but in mindset too – herein lies the promise of a better tomorrow. It is in the ritualised negotiation of ways of working that change manifests and sustains an organisation moving forward. Living in a DELA world Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter first formulated the term ‘creative destruction’ in 1942; a time nearing the 3rd industrial revolution and at the height of the Second World War. He described it as: "the process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one." While this is often associated with the development of capitalism, it could be useful in its application when thinking through our own ways of working today. Especially considering that we find ourselves at a similar pivotal moment; entering the 4th industrial revolution and situated in the middle of a global crisis. We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that is unfolding, and to shape our own narrative going forward. Our world requires a deliberate dismantling of oppressive, exclusive, or passive practices, to allow for an emergence of improved, inclusive, and active processes. We need to commit to making shifts in our business spaces, realms of work, or spheres of influence; even if just incremental change, it matters. We need to break free from the constraints of normal. This was originally published on Marklives

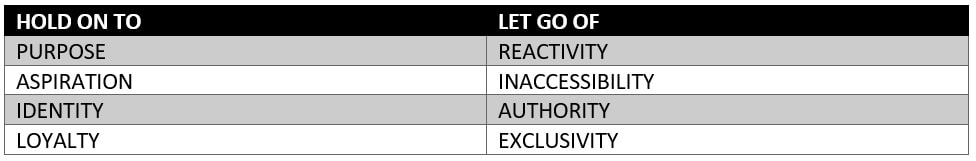

What if we viewed competition as a motivation, not a set-back? First with your head, then with your heart Counterfeit, imitation, fake. A nightmare for any brand, especially a small business that lacks the means to fight back. This was the reality earlier this year for a South African clothing brand. A family business spanning generations and built on the purpose of delivery bespoke apparel to an exclusive audience. This was not a contender in the same weight division as Nike, Adidas and the like. What seems to happen, as the brand gains popularity and prestige, it becomes more susceptible to imitation. A futurist, Xolile Martin, had been offered a counterfeit of this local brand’s products. It was being sold in China Town malls and online platforms such as Facebook and Whatsapp. He alerted the brand of the fakes circulating at a fraction of the original’s cost. Understandably, the brand was shocked. The challenge seemed impossible to tackle. They decided to take a legal approach; warning its online audience of fakes, announcing their collaboration with authorities, and encouraging people to only buy through official channels. Living in a DELA The commodification, fetishisation, and appropriation of culture is a delicate, entangled, thorny problem. Essentially, brands create and shape culture – in terms of behaviour, values, aspirations, identity, and more. For those who are deeply rooted in legacy or have strong heritage connections, this requires further consideration and contemplation for how one disruption, change, or intervention could impact an entire ecosystem in which it exists. We can apply the DELA framework to help us make sense of the story that is unfolding, and to shape our own narrative going forward. Rather than fighting against something, brands have the choice to fight for something; to create a new consumption space, to tap into another audience, and to draw on localised trends. This is an opportunity to connect with people and ideas in a way that builds long-term relationships, calls them to action, and instils a sense of collective purpose behind a shared vision. Originally published on Marklives

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed