|

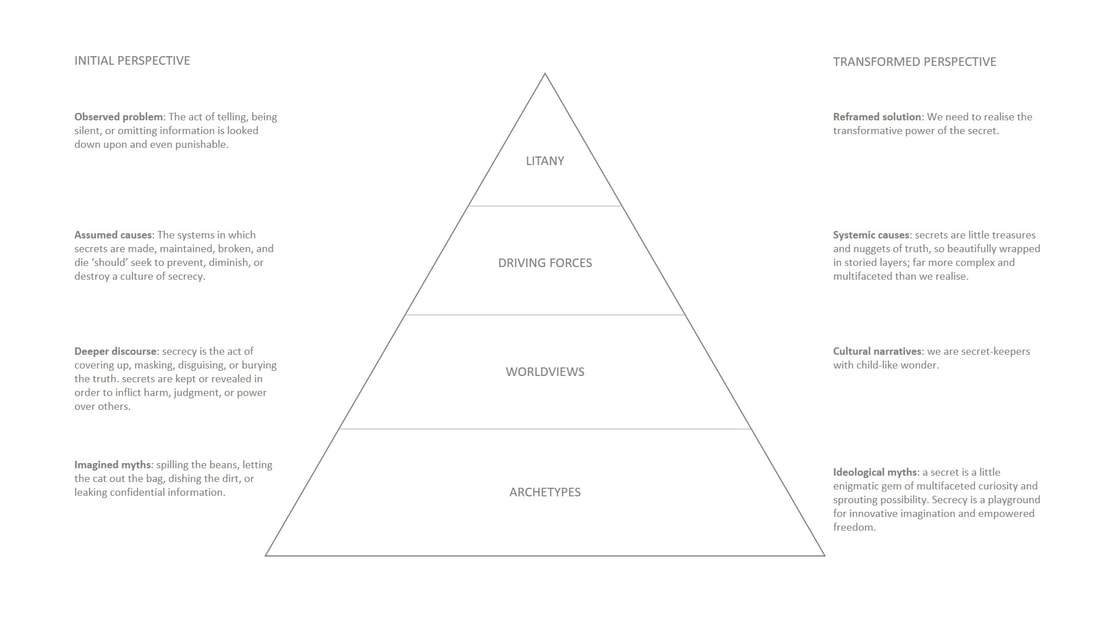

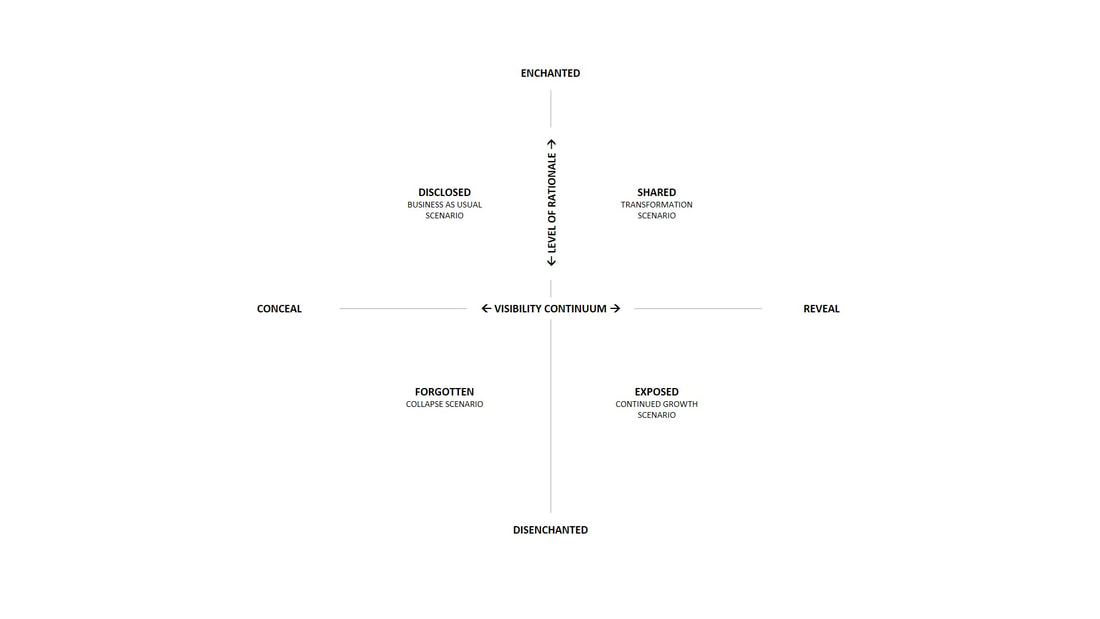

There was a time when the world was enchanted; entangled in living stories of mystery, magic and wonder. This was followed by the refashioning of modes of historical thought; the Age of Enlightenment. A time characterised by science, logic, and reason. The mechanisation and intellectualisation of life is believed to have led to a disenchantment of the world, as proclaimed by sociologist Max Weber. The world is becoming more explained and less mystical. Modern society seems to rationalise cultural practices and devalue belief systems, severing the link between humanity and nature, the real and imagined, the actual and the possible. Have we lost our ability to get caught up and carried away in a state of wonder? A counter-argument is that “enchantment never really left the world but only changed its forms” (Boje & Baskin, 2020). Do we remember what it is to be curious about the unknown? What is something in our everyday lives that goes beyond that which is shown and told? It could be argued that secrets are a form of enchantment, and the organisation (or work environment) a context in which secrecy emerges and secrets are contained. What are the contemporary currents of thought on the secret in a rapidly changing world (Manderson et al, 2015)? This paper seeks to explore the life of secrets in organisational institutions and structures; their purpose and potential. Hidden in plain sight Historical moment and geographical location are key determinants in what is considered acceptable behaviour when it comes to secrets and secrecy. Secrets are composed of subjective interpretations, organising principles, forms of knowledge production, circumstantial conventions, interacting players, inherent intentions, and elements of control. It is through secrets that we can create identities, negotiate intersubjective lives, regulate social interactions, and frame institutional practices (Manderson et al, 2015). In the past, secrecy was associated with unfavourable notions of dishonesty, evasion, elusiveness, scandal, gossip, espionage, confusion, contradiction, betrayal, and repression. It was not considered common practice, or at least it was largely hidden from view and public knowledge. Keeping and sharing secrets later became attached to ideas of closure, intimacy, liberation, justice, healing, forgiveness, and contributing to change. Is the development of a secret not a form of knowledge production, and its circulation not a mode of knowledge sharing? By definition, gathering knowledge is a process of extracting, translating, and making visible that which is coded or hidden. A secret could be seen as a form of knowledge invested with value; an orchestrated construction of knowledge that guides engagement and therefore an understanding of truth and its interpretations (Manderson et al, 2015). In applying Sohail Inayatullah’s Causal Layered Analysis method we can unpack the layers of secrets and the associated narratives used to make sense of secrecy. The very first layer, the litany, is the observed or obvious idea, second is the systemic causes or driving forces that create the conditions in which the idea exists, third the discourses and ideological assumptions that legitimise and support a worldview, and fourth is the layer of myth and metaphor that is linked to long-term history and emotive dimensions (Coetzee, 2021). Instinctively, many of us would conjure up images of spilling the beans, letting the cat out the bag, dishing the dirt, or leaking confidential information when we think of telling a secret. In this sense, secrecy is the act of covering up, masking, disguising, or burying the truth. With a worldview skewed towards a negative secretive bias, it is easy to justify that secrets are kept or revealed in order to inflict harm, judgment, or power over others. The systems in which secrets are made, maintained, broken, and die then seek to prevent, diminish, or destroy a culture of secrecy. The act of telling, being silent, or omitting information is often looked down upon and even punishable in such a context. How can we view secrets in a different light and even use them to our benefit? If we were to view a secret as a little enigmatic gem of multifaceted curiosity and sprouting possibility, we could imagine secrecy as a playground for innovative imagination and empowered freedom, and us the secret-keepers with child-like wonder. The little treasures and nuggets of truth, so beautifully wrapped in storied layers. We would come to realise the transformative power of the secret. Like a thief in the night Secrecy is not a form of solipsism - a self-centred or selfish act of benefiting, prioritising, or justifying the self. Instead, a secret is something that is partially known in order to attract attention and create an air of importance around that which is unknown (Bigo, 2019). In other words: content is strategically masked in order to announce its existence. Secrecy becomes an attractor; enticing those eager to know more. Attractor, in the way that Dave Snowden discusses the concept, is a phenomenon or pattern formation that arises when systemic conditions create possibilities adjacent to an existing situation or reality. As an attractor begins to resonate with those in a given context, and gain momentum, there is a structure and coherence that emerges. People and behaviours are nudged in a particular, intentional, prefered direction. Using the STEEP framework we can gather and organise signals and insight relating to secrets and secrecy, here and now. Understanding secrets in context could help us map out possible scenarios for the future of secrecy and its place - its location and role - in the organisation. In the social realm we see trends around human development in the direction of re-enchantment, healthy forms of secrecy that enhance well-being, education and training around secrets as catalysts for change, and the role of secrets in identity formation, group belonging, and relationship building. In the technological realm there are dominant trends of connectivity and communication being shaped by and centred around data sharing and privacy. In the economic realm secrets become competitive commodities with a value that lives and dies in its circulation. In the environmental realm secrets are a resource once deeply rooted in our connection to nature; through myth, metaphor, folklore, and sacred knowledge. Secrets have become uncharted territories that some seek to explore and exploit. It brings into question the abundance, scarcity and sustainability of secrecy in today’s world. Finally, the political realm provides insight into the implications of secrecy in a globalised, polarised, and marginalised context. Protectionism and mistrust come into stark contrast with integration and social cohesion when secrets are regulated and used as weapons in conflict. Social realm “The big idea is that if you want to change the world, you need to enchant people,” says Guy Kawasaki (2011). In the context of the organisation, disenchantment - in its capacity to explain away the mystery of things - has resulted in increased knowledge and enhanced social and material control, but also a greater impersonality amongst individuals. As the argument goes, according to Weber, rationalisation is responsible for many advances - technological and social - but it has also potentially dehumanised individuals as cogs in the organisational machine. Traditionally, secrets differentiate between insiders and outsiders; those in the know versus those in the dark. Research has shown that secrecy has a binding and bonding effect. It is in sharing secrets that we establish our own identity, create a sense of belonging with someone else, and nurture a form of intimacy with those entrusted with a secret. Secrets are situated in relations; they build, sustain, and convey connection between people (Manderson et al, 2015). While secrecy may elicit suspicion, competition and exclusion, it can also foster alliance, transparency and collaboration. Tech realmWe live in a highly globalised and mediated time. There is an increasingly complex relationship between public and private spheres. Sociologist Edward Shils asks: If everything is knowable and private life transferable into public spaces - what then is public life? What sense do we make of a hybridisation or of the invasion of private life into the public domain? On the other hand, sociologist and philosopher Georg Simmel claims that as societies become more complex, what is public becomes ever more public, and what is private becomes ever more private. Either way, secrecy further complicates and destabilises the dichotomy of public and private, internal and external, known and unknown. Post-industrial worlds - those that depend more on services than on the production or manufacturing of goods - are heavily influenced by technology. The quantity or scale of data generated and captured, along with the rate or speed of data circulation is accelerated and escalated by technology. Secrecy comes into play in our digital and virtual impression-management and fantasy creation; living a highly digitised life creates the illusion that there is no space for silence and undisclosed secrets (Manderson et al, 2015). Some might say that technology has contributed to the death of the secret; that big data displaces and prevents the possibility of the secret. As data is collected, contained, and dissected, it becomes possible to govern, manipulate, expose, and monitor those from whom the data is taken. What if we choose to openly share our secrets? Social media provides a platform where private lives enter the public domain. Personal profiles become publicly curated archives of the self; supported by confessional media culture. Economic realmThe appeal of a secret lies in its contextual relevance as well as the continuum of ignorance that it generates (Bigo, 2019). It is not a clear-cut distinction between ignorance and knowledge, but rather a range of knowing, not knowing, pretending to know, claiming to know, and feeling entitled to know. In Anthropology, gift-giving is seen to be a complex system of exchange that involves history, reciprocity, sentimentality, and obligation. Could the same be invested in the sharing of secrets? Government and big business are carried out in secret. Whether its state secrets or trade secrets, there is commercial viability and financial risk mitigation inherent in the maintenance of ignorance, the privatisation of information, and the materialisation of the secret. According to Simmel, the value of the secret is intensified by the possibility of its betrayal or revelation. An unintentional consequence of this, however, is that it mobilises appeals for transparency (Manderson et al. on Erikson, 2015). Transparency itself can even be considered a commodity that often benefits the state, its citizens, private capital and urban rich (Nuttall & Mbembe, 2015). Environmental realmVarious academics, historians, sociologists, and others, seek to “re-enchant forms of modern capitalism that have separated people from nature, through the Cartesian/Newtonian worldview” (Boje & Baskin, 2020). According to these experts, enchantment resides in many living storied spaces. It is this interplay between space, secrecy, and story that enchantment can be found. In a way, organisational institutions and infrastructure - both physical and virtual - become sites of secrecy; its production, growth and decline. Political realm There are moral, intellectual and epistemological complexities and implications inherent in secrecy. There is a politics and ethics of owning, exposing and inspecting things that are secret, honoured, and sacred (Manderson et al, 2015). This raises concerns around privacy, confidentiality, rights, care, anxiety, control, policy, legislation, and responsibility. Those who hold secrets wield power. Secrets can be used to reinforce power asymmetries, or they can be harnessed as a form of resistance and trigger for revolution. In a way, secrecy is capable of disturbing and redistributing power. Similarly, exclusion from knowledge “tracks the topography of power” (Manderson et al, 2015). Rage against the dying of the light Using scenario development we can formulate stories of future possibilities. What are the hidden futures of an organisation as it relates to secrets and secrecy? If we were to map a line of uncertainty and a range of impact, we could develop four potential future scenarios. On the horizontal axis: a continuum of invisibility and visibility; from concealing to revealing. On the vertical axis: a movement between imagination and rationalisation; enchantment and disenchantment.

Let wonder be reignited What can be learned by inviting collective and self-reflection around secrecy (Manderson et al, 2015)? Imagining and building futures, of course. Boje and Baskin (2020) make a critical distinction between enchantment by design and enchantment by emergence. Enchantment is characterised by organic participation, not of mechanical observation (Berman, 1981). Some (Max Weber and Friedrich Nietzsche in particular) view Enchantment as a time of superstition and unreasonable fear. Others (such as Morris Berman, Thomas Moore, and George Ritzer) view Enlightenment as the elimination of wonder and meaning from the world, and an introduction of alienation and destruction of the self. Many agree that the dominant narrative of modern life “no longer holds forth the wonder of an enchanted world” (Boje & Baskin, 2020). Enchantment by design refers to how the individual’s experience is shaped by the groups’ dominant narratives (Boje & Baskin, 2020). Enchantment by emergence is a deeply personal state of wonder in which individuals are able to be both caught up and carried away (Boje and Baskin on Bennett, 2020). What will our organisations decide? Lessons for organisations

This article was written for IFR

0 Comments

Imagine a world where humanity and technology merge seamlessly into a single entity. Does this invoke fear or hope? If you imagine a world where technology replaces people in spaces of work or even rises up against humans in an apocalyptic display – you would no doubt, feel a sense of fear. However, if you imagine a world where technology enhances human ability and extends our lifespans, you might feel a sense of hope. In a critical reflection of transhumanism at the IFR’s 7th colloquium, Morgen Mutsau, from the Centre for Applied Social Sciences (CASS) at the University of Zimbabwe, shared a decade’s worth of research into a human-based information system. Central to Mutsau’s argument is that a limited knowledge of computing results in a restricted understanding of and preparation for transhumanism. In other words: we don’t know what we don’t know, and we cannot effectively prepare for the unknown. Another area of focus in Mutsau’s argument is the idea that the human being has the same data processing architecture and behaviour as that of a computer. In drawing parallels between humans and computers, it is important to note that they have shared capability, but are still distinguishable from one another. “On the issue of intelligence, who is really intelligent?” Asked Billy Matsitse, a participant at the colloquium, “The human being that creates the computer? Or the computer that takes what the creator has done and advances it?” On a similar note, Nyambura Mwagiru added: “The autonomous nature of this creation of the mind depends in my view on its ability to perceive, to discern, and to learn. As learning systems, computational creations of the human mind can become learning systems.” So, in the end, the enhancement of human ability by technology does not mean a replacement of human essence and importance, and the learning or self-generating nature of intelligent technologies might at times surpass human intelligence, but it does not ever fully sever itself from its human creator. Perhaps it comes down to the computer as mediator of knowledge, and the human as generator of knowledge. For now, at least. On a human level With technology infiltrating into every aspect of our lives, how do we define what makes us human; distinguishable from our digital selves and mechanical tools? “From computing to competing: from a species competitiveness perspective, the best way for humans to compete with computers (apart from collaboration) is to behave like a human”, offers Dr Morne Mostert, director of the IFR. Both the human being and the machine computer have the capacity to remember; to encode, to store, and to retrieve memory. So, are we all that different? In short, yes. Since the 1970s, organisations have been understood largely in terms of the machine metaphor; a closed system of hierarchy, control, authority, networks, and commands. Essentially, understanding human beings and human institutions as a type of computer based on efficient algorithms, we would be able to solve problems, make improvements, and create change in the human world, in the same way we would in the digital and mechanical worlds. However, there is risk of oversimplifying in reducing everything to its core algorithm. This thinking is now being applied to humanity in the form of a transhumanist movement. Transhumanism, says Mutsau, is a transcendent process of moving from one state to the next. Post-humanism, he explains, is the society that exists in the aftermath or era after transcendence. On a cultural level Macro-computing, according to Mutsau, has the potential for programmability, corruptibility, and correctability. In the human world, this idea of acquiring and adjusting skills, information, and interactions takes the form of ‘culture’; loosely defined as shared values, beliefs, experiences, communications, and behaviours. Corruptibility often takes the form of conflict, or results in such. Arguably, central to all conflict, is power. Computers, like humans, operate on power – in the literal sense of needing a power supply to function, but also in a metaphorical sense where, for example, you find the problematic use of ‘master/slave’ narratives to describe an asymmetric communication or control between devices or processes. As Doris Viljoen, senior futurist at the IFR, noted: “Computers were, and still are, designed to mimic human information”. We should then be more considerate of the information and behaviour on which we model these systems. We should also question and anticipate the cultural implications computing might have on humanity in return. This raises ethical concerns for rights, obligations, accountability, responsibility, risk, prioritisation, choice, and so much more. On an individual level Endo-processing micro-computing, Mutsau explains, makes use of an internal, localised processor; for the human being it is their brain, and for the machine computer it is their CPU. Modelling the human being as a computer organism reveals that both entities are capable of executing data input, processing, and output functions. This I-P-O algorithm (input, processing, output) is considered to be universal and translatable into different contexts or scenarios. The problem, however, is that this linear perception of the relationships between cause and effect – reducing a problem to an issue of function – places this discussion firmly in the ‘simplicity’ realm of the cynefin framework. It reduces the complexity of what it means to be human – our personhood, our agency, our individuality, our choice – and further reduces our understanding of or preparedness for technological advancement. Conclusion Instead of human-centred design, this colloquium skewed towards a computational focus – mechanising the human, rather than humanising the machine. Computers operate in binary – it is either true (1) or false (0). We cannot limit humanity to binaries. We exist in flux and fall on spectrums. Comparing men and women and their assumed black-and-white computational capacities, “in a non-binary world where we have trans and intersex individuals too, I wonder what the computational capacity is for these persons?” asks Dr Njeri Mwagiru, senior futurist at the IFR. “We now know that human bias is being programmed into the algorithms, and replicating societal ills in the artificial intelligence realms”, says Dr Nyambura Mwagiru, a participant at the colloquium. Whose wisdom, intelligence, and knowledge systems are we drawing on when developing technology

This article was originally published on IFR

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed