|

In a post-truth era, a time where intuition trumps intellectualism, consumers are looking to connect with products that they can relate to — something that resonates with them. It’s time to transcend the boundaries of consumer and product truths, and look for those universal motivators behind consumer behaviour: the human truth. The truth is... A product truth is often a message communicated about, well, the product: what it is and what it does. It’s intended to assist consumers in forming or altering their perspective and opinion of a product or brand. A human truth goes beyond the product and category; it explores the socio-cultural world of the consumer to try and understand what motivates their behaviours and perceptions of products and brands. Inspired by growing interest globally in genetics, heritage, and lineage, Marmite in the UK recently released a “Marmite Gene Project” advert. This shows a series of scenarios in which different families receive the results of a Marmite test, which determines whether they were born loving or hating Marmite. As a product, Marmite knows that it is either appreciated or despised for its distinctive taste. As a brand, it has often drawn on this, its very own human truth. It so cleverly resonates with both lovers and haters of the product that it becomes irrelevant, whether or not you like it. The brand and its communications connect more strongly with something that goes beyond personal taste. Alternatively, if the product or brand doesn’t speak to a universal human truth, there’s the option of applying culturally relevant research and communication methods. Ethnographer and researcher, Anya Evans, used Tinder as a methodological tool to reach people who were difficult to connect with. Applying the principals of Tinder (namely, the way it operates by gathering data about individuals, and connecting those individuals with people in search of specific criteria), Evans was able to navigate through the restricted field (Occupied Palestinian West Bank) and interact with the people within it. Imagine the possibilities for market researchers and advertisers looking to communicate with hard-to-reach consumers by simply using the technology that people are already using. Why be limited to human truth and cultural method; why not use both? IKEA is on a mission to “put people first”. In an extensive ethnographic study, IKEA sent researchers on home visits around the world to better understand what “domestic bliss” looks like culturally and geographically. This hasn’t only informed its product innovation; it’s given it them a clearer idea of who its consumers are. We all have basic needs, desires, and preferences that manifest in different ways. It’s up to the marketer to uncover these human truths; it’s the task of the advertiser to effectively communicate them; and it’s the brand’s mission to connect with a human truth. This article was published on Marklives

0 Comments

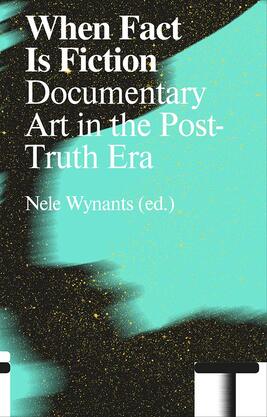

Today’s consumers are bombarded with facts, falsehoods and fabrications; they have to filter through fake news to decipher what is factual and what is false, and avoiding click bait that uses sensationalist techniques to get them emotionally invested to read further. In a post-truth era, facts become questionable, consumers grow sceptical, and brands draw inspiration from a multiplicity of perspectives. Fact. A fact is something that is assumed to be true; it is presented as a statement of truth. This kind of statement is told in somewhat of an authoritative narrative, with a confident use of tone and wording. It seems to be convincing, unopposed and true in its entirety. American cable network, A&E, released a Brave Storytellers campaign in August 2017 as an attempt to rebrand the network as a platform for “serious storytelling”. It wants to be viewed as the home to “fearless and factual storytellers”. The campaign features personalities from different shows on the network, each with a tagline that captures — in a factual tone — what each show is about: we are not victims, we are not limited, we are not afraid. Making statements of what they are not, the overall campaign concludes that they all represent the network; they are A&E. The campaign leaves little room for debate or challenge. Fiction. Evidence is traditionally used to determine whether a statement is true or valid. What, then, of a post-truth world where validity is determined through a process of psychological factors, rather than knowledge-based ones? It is common practice for those operating in a post-truth context to judge the truthfulness of something based on how that information makes them feel. If something feels right, correct or true, then it must be so. We see fiction and fabrication play out in an interesting manner when it comes to false advertising — whether justifiably questionable, or assumed to be. While some are often content to accept what is advertised to them or are even aware that some advertisers fabricate truths in order to convince them to buy into a product or service, there are others who demand evidence. In August, Africology, a cosmetics and spa company originating from Johannesburg, was ordered by Advertising Standards Authority to withdraw its advertising claiming that it did not test its products on animals, as there was no evidence provided to prove it. Its rabbit logo is placed on products that contain ingredients tested on animals; it’s apparently not meant to validate its anti-animal testing policy but some feel that this is false advertising. Somewhere in between. What does this mean for brands? Advertising is an art. Sometimes art imitates life, and sometimes life imitates art. Be clear about what message you want to communicate: are you depicting an imagined ideal (life imitating art) that consumers are aware is fictional but strive towards, or are you painting a picture of your brand’s truth (art imitating life) that is a reflection of the consumer’s lived reality? Be confident in your statements and communications, but be wary of sounding authoritative and elite. This article was published on Marklives

Stop pretending… In a commercially competitive and culturally chaotic world striving for better, faster, more, consumers the world over are selective in what they believe, particular about what they choose, and overwhelmed by information and options. As a kind of defence mechanism, consumers are more sceptical and even more difficult to convince. So, instead of trying to persuade them with false hope and empty promises, be direct, provide a platform for conversations, and align your marketing or advertising with the values the product represents. Stand your ground We are seeing a rise in populism (where ordinary people are at the centre of focus in media, art, politics, and more) and a decline of trust in a privileged elite. This is happening in international markets, and locally with people such as Julius Malema and the EFF appealing to the working class (wearing similar uniforms and taking a stand for matters that concern the average South African). But… there are exceptions. For example, where does US president Donald Trump fit into this? Trump is the very definition of a privileged elite — and yet he appeals to the masses, to the ordinary person. Just as BMW represents for many the drive and ambition to succeed, and Mercedes Benz the indication of having arrived, — public figures (such as Trump) are a brand themselves, and anyone who associates with this brand carries with them the labels that it entails. Earlier this year, Kellogg’s decided to retract all its advertising from the online news platform, Breitbart News Network. The brand’s reasoning for doing so was that its values didn’t not align with what it believed Trump’s to be, and Breitbart seemed to broadcast these less-favourable ideas and ideals to an audience supposedly supportive of that. Breitbart’s response was to stand its ground and begin a social media boycott movement: #DumpKelloggs. Transparency trumps deception Rather than publicly slamming or insulting a person or brand — and ultimately its supporters — it would be best to indicate what one does stand for. Nando’s, the Portuguese-themed food chain originating in South Africa, has outlined very clearly where it stands on particular matters, and how it implements this through its brand and product. Its transparency gains trust and its values translate into customer loyalty. Honesty is bitter sweet Taking a stand doesn’t have to mean being overly serious or repositioning your brand in order to communicate a thoughtful message. Ben & Jerry’s, popularly known for its ice cream, is vocal on social issues but in a way that’s true to its brand. The way that it communicates its opinions and information on issues or current events is powerfully to the point and easy to understand, and it is also accompanied by illustrations to make it seem less intimidating or daunting.The key is to be direct, transparent, open and honest — but with substance. There needs to be purpose behind your communication. Be wary of who you associate with, what you draw on, and what you refer to in your advertising. Stay relevant by adapting to shifting global narratives. This article was published on Marklives

Brands have their own truths, and it is up to the consumer to decipher and determine which truth they relate to, agree with, or discard altogether. A truth You have two children. You share between them a chocolate bar, giving each half. They run outside to enjoy their treat in the summer sun. In the heat, as they play, the chocolate begins to melt and one child accidentally knocks the remaining chocolate in the other’s hand to the ground. There it lies, a melted misshapen mess of sugar and dirt. The latter child instinctively grabs the chocolate out of the former child’s hand, declaring it now belongs to them. The former child begins to cry and calls for you. Not knowing what had taken place, you walk over to the scene with no idea of what to expect. The self-proclaimed victim who had their chocolate removed from them explains through tears that the supposed thief had unfairly taken their treat. The supposed thief counters this argument by blaming the apparent perpetrator for having initiated the series of events by bumping into them in the first place and making them drop their treat to the ground — claiming that this chocolate therefore belongs to them and that the so-called victim got what they deserved. You, as the parent, now need to make a decision. Both your children feel strongly about their truth — their opinion, perspective and experience — of the truth — the actual events as they happened. Do you feel confident in either truths? Are you skeptical of either or both? Do you feel apathy or sympathy towards your children? Who do you believe? It is the same with advertising and marketing. Brands are like these two children; they operate in the same environment, but get different reactions from the consumer (the parent). Brands have their own truths, and it is up to the consumer to decipher and determine which truth they relate to, agree with, or discard altogether. The truth A few years back in 2013, FNB found itself in an epic quest. As with any hero journey in literature, the hero — FNB — was called to embark on this venture. What inspired FNB was its realisation that the South Africa it had dreamed about and been promised in ‘94 was not the South Africa it believed it was living in at present. FNB took it upon itself to capture and expose socio-political injustices. It filmed unscripted interviews with 1 300 South African youths in which the teens and young adults expressed their political opinion — notably their dislike or even distrust of the ruling party and present government. FNB was entering unchartered territory; it was at the threshold of the known and the unknown. It was the beginning of its transformation from what consumers generally considered to be a relatively conservative bank with ties to the country’s past to conquering its own demons and braving the storm. FNB was on a mission to inspire South Africans to unite and stand together in creating a better country. From the interviews, according to CMO Bernice Samuels, FNB extracted themes and messages which were then incorporated into a scripted TV advert. This would be a first for both FNB and SA — not only would it blatantly voice FNB’s opinion of the country’s current state, it would do so live and in real time across channels and streamed online. But the ad had been presented as being an unscripted, filmed event at a school in Soweto where a teen voiced her opinion. After it was revealed that it had been staged, the public felt deceived by the bank. In addition to this, it lost popularity among those who didn’t support its version of the truth. FNB received further criticism for withdrawing the ad and unscripted interviews that had been posted online. In trying to give a platform to unheard voices, its own voice was silenced. Some critics stated that FNB should have followed through with its mission; if you make a political statement, stand your ground. But, alas, the hero had fallen victim to challenges and the temptation of surrendering. FNB attempted to reach the atonement stage of the hero journey by taking out full-page ads in local newspapers that were written in free-verse and in a positive tone: “We help because we believe where there’s help, there’s a way.” Where the truth lies Some market researchers and analysts believe that this campaign was merely an attempt made by FNB to cut through the clutter that consumers are surrounded by. With shorter attention spans and a huge selection of choices, consumers are easily distracted; their attention divided and their loyalty wavering. So how then do brands share their truth without facing dire consequences? Nando’s is known for its subtly witty social commentary. It draws on the power of suggestion and makes tongue-in-cheek statements. But it is not immune to negative public opinion nor to consequence; it, too, has had ads pulled and has had to make public apologies but it’s been consistent in its perspective and standpoint. A safer — yet effective — approach was adopted by SA Home Loans. Here, the company put up billboards displaying consumer quotes. Drawing on the ongoing trend of consumer reviews and the impact of eye-witness accounts or first-hand experience, SA Home Loans quoted satisfied customers alongside the statement: “their words, not ours”. This makes SA Home Loans’ truth seem more believable and trustworthy. The key is to allow for a diversity of voices to be heard, rather than simply raging against the machine with no clear intentions. Be transparent and stand your ground. Know what you are fighting for, and follow through. Yet know when to acknowledge your mistakes and take responsibility for your actions. Your truth is not fact; it is merely a truth among many others. This article was published on Marklives

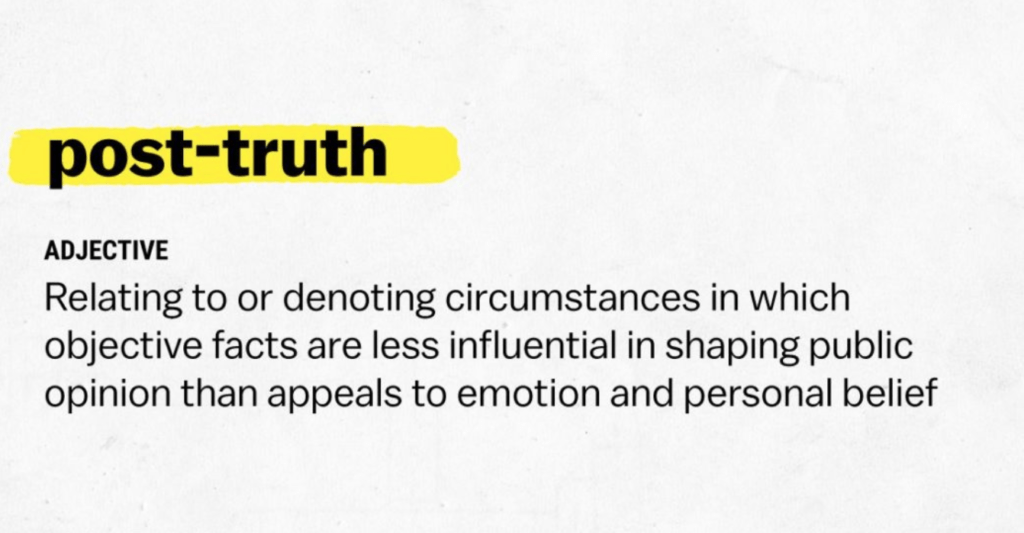

Consumers don’t live in a vacuum, nor do marketers operate in a static space. We change with the times and adapt in order to survive in an increasingly globalised and competitively commercialised world. So how then do we effectively communicate product truths in a post-truth era? How do we address consumers’ concerns with what is real, trustworthy, reliable and true? We live in a post-truth era... “Post-truth” here doesn’t mean “after the truth”, but rather a time in which “the truth” (or truthfulness) has become relatively irrelevant. It brings to light issues of representation, objectivity, description, culture, authenticity, power, and more. People are making decisions and judgments based on how they make them feel, rather than what the supposed facts are behind it. We want transparency, but what we get is a truth concealed; we’re deceived and confused. …where we value not the truth, but multiple truths… In a world where feeling trumps fact (pun intended), we see either a loss or collapse of meaning, or a reworking and repurposing of it. Online platforms give everyone a voice, allow for mass consumption of fake news, and disconnect us from the real world. We value things not for their accuracy and we don’t measure their importance according to how long it stays in collective memory — instead, we determine its value according to how many times it was shared and how many people saw it. It’s a popularity contest in a world of convenience. We accept without questioning and believe without weighing up the facts. Thinking delays things — we want instant gratification. …and we are writing our own truths... We want snapshots, not stories, but we don’t want to be denied participating in the rewriting of the social narrative. The global narrative being told is one that makes new connections — linking the previously considered rational, reasonable, intellectual, elite and scientific to one another. In a post-truth era, experts are knowledgeable and therefore less trustworthy. Consider the relatively recent boycott of Spur by various social groupings for different reasons. The boycotts are fuelled by what each group considers to be ‘the truth’ but is their version of the truth; a truth. One truth was captured on CCTV footage. In short: a white male is seen grabbing a black child, in what some call ‘an aggressive manner’. The child’s mother confronted the man with what some have said was ‘inappropriate language’. The man then made a verbal threat to the woman. Consider a truth to be a perspective and an experience of an event. Everyone involved, although experiencing the same event, has a different reception, recollection and interpretation of it. These truths, whether lived experiences, eye-witness accounts, or simply personal judgments, were interpreted and communicated in different ways to convey particular messages — depending on which truth was believed or favoured. A “Boycott / Boikot SPUR Steak Ranches” Facebook page adopted the truth that a white man was banned from Spur for his actions, while a black woman was praised for her supposedly racist remarks. Kyknet further portrayed this truth by airing only the woman’s verbal attack on the man, and not the part of the footage that showed him grabbing her child. It became a truth focused on racial tensions. An opposing truth was shared on Twitter where people wanted to boycott Spur because the staff members present at the time did nothing to protect the child or assist the woman and didn’t believe her truth as she had experienced it. Chief operating officer of Spur, Mark Farrelly, revealed the source of and concern behind this truth: “It was an assault by a large male on a young child. It shouldn’t even be reduced to a question of race. The aggression that lies under the surface in this country is crazy. The abuse of women and children in this country is pandemic. We are not going to sit by and allow one of those things to happen. I don’t think it’s appropriate to take a middle road: badly behaved individuals should not be allowed to eat in family restaurants.” … in this kind of environment, how do brands react? In a world where consumers question what is real, trustworthy, reliable and true, they react first with their heart and then with their head. As marketers and advertisers, we should take into consideration our consumers’ context, learned behaviour, and world views; we need to adapt and change with the times in order to remain relevant. We should speak from the heart, to the heart — give consumers something to connect to in an ever-shifting and drifting world. We need to be aware of how we communicate, and what messages we attempt to get across. Our consumers are dynamic beings that live in a fluid context — our products, brands, communications should speak to that. This article was published on Marklives

|

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed