|

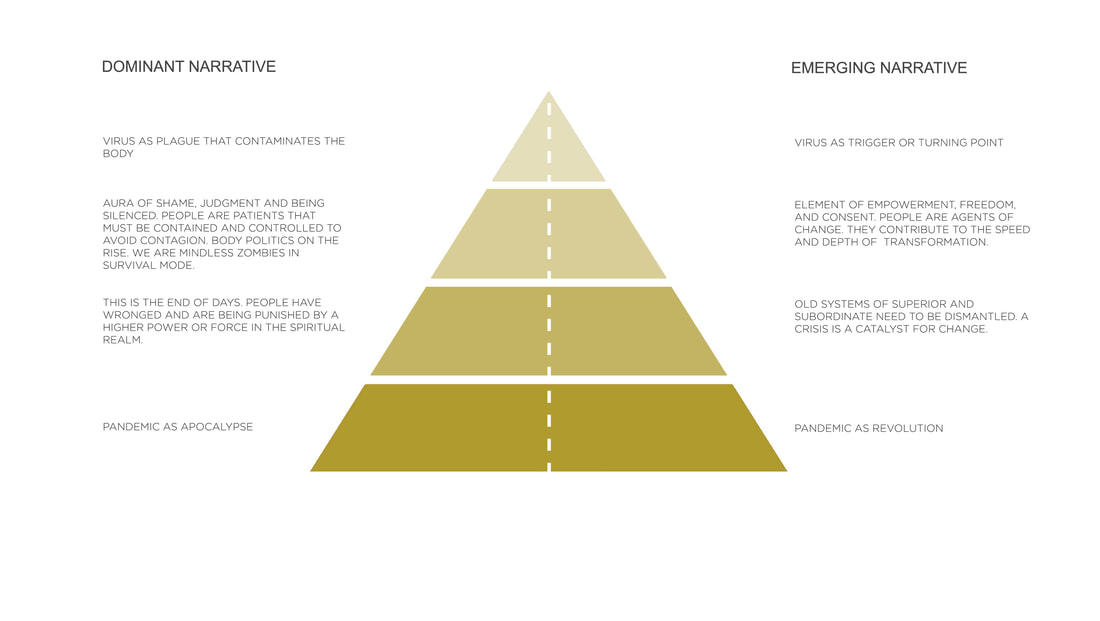

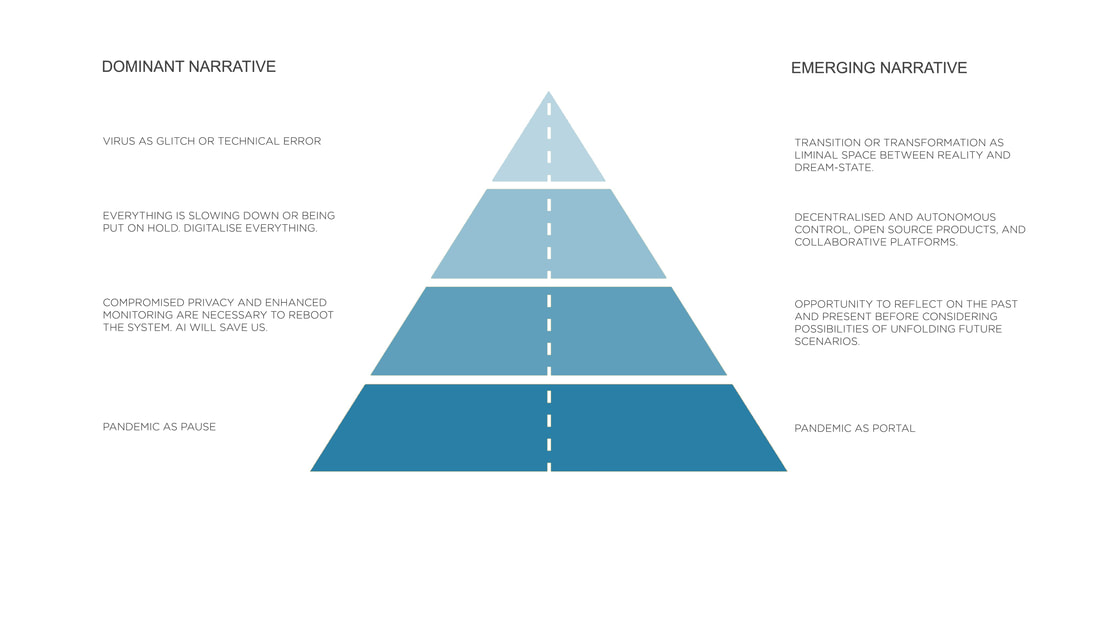

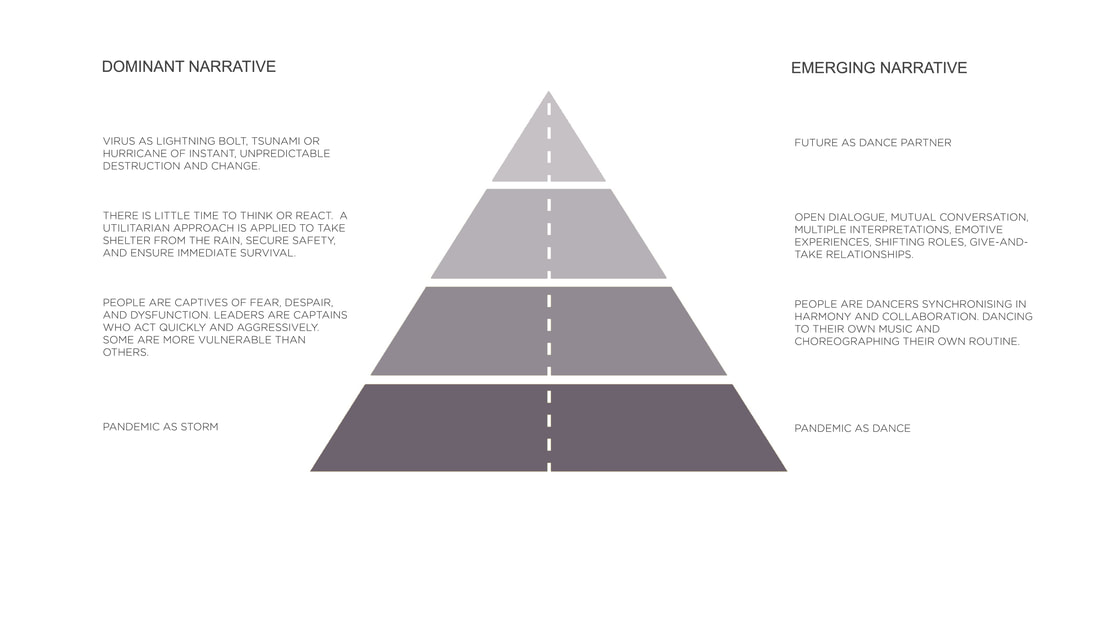

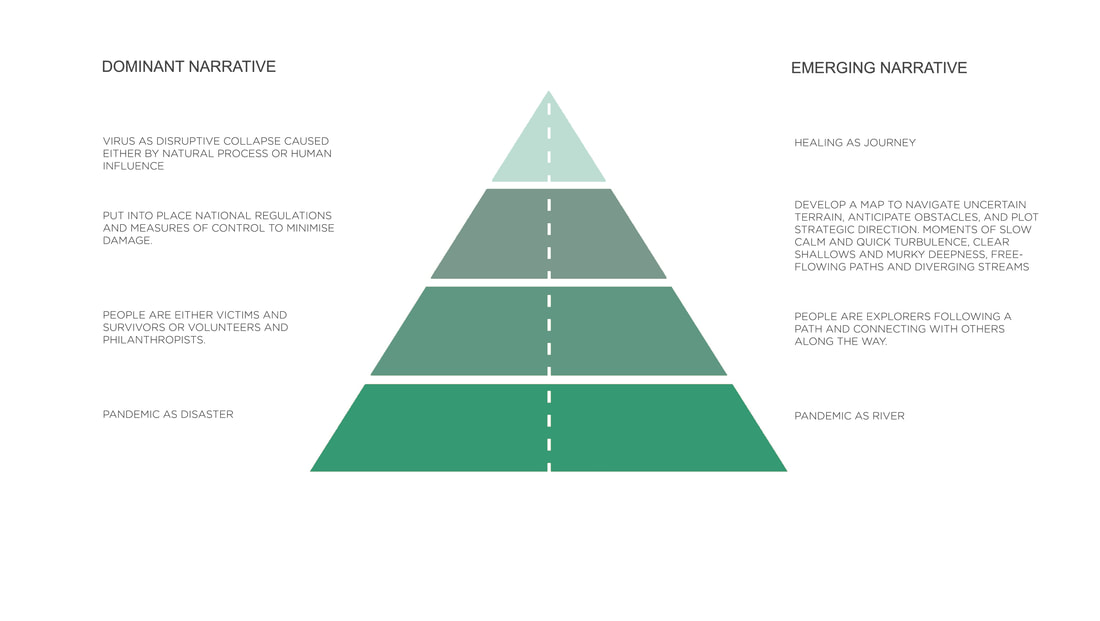

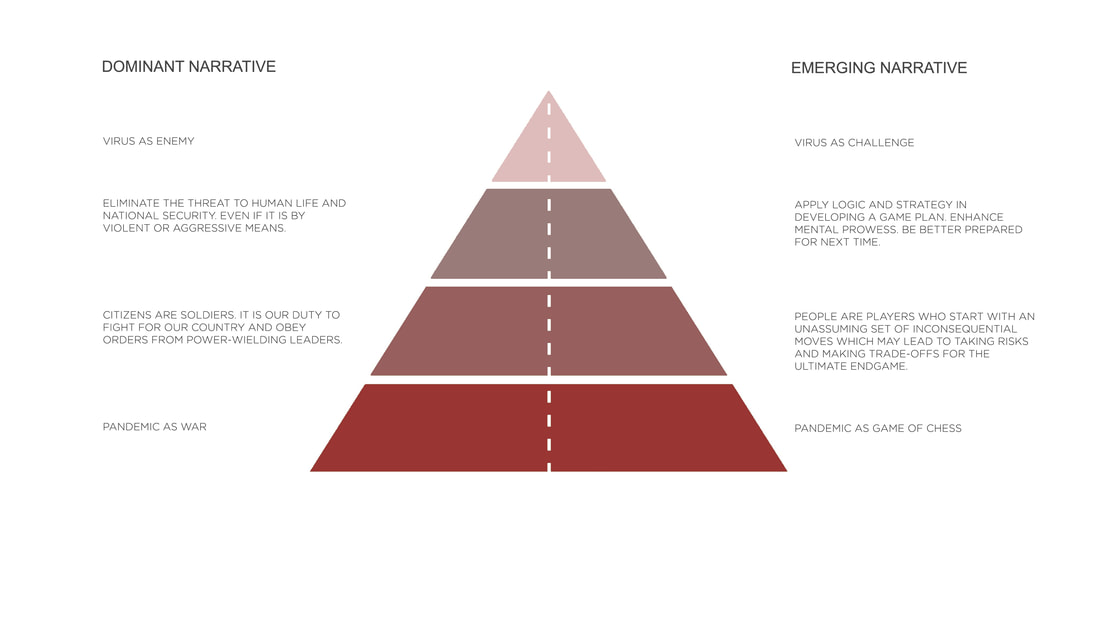

In Hindu mythology, it is believed that the Earth is balanced on the backs of elephants, which are themselves supported by a World Turtle. Below that turtle? Another turtle. It is turtles all the way down. In complexity and systems thinking, it could be argued that a proposition requires justification, and the justification itself needs to be supported. No idea exists in isolation, no truth in a vacuum, no experience untethered from others. It is turtles all the way down. By identifying layers of analysis, Causal Layered Analysis is a sense-making tool that explores the narratives used to make sense of the world. The very first layer, the litany, is the observed or obvious problem and resulting official future, second is the systemic causes or driving forces that create the conditions in which the problem or future exist, third the discourses and ideological assumptions that legitimise and support a worldview, and fourth is the layer of myth and metaphor that is linked to long-term history and emotive dimensions. In addition to developing an understanding of the world, it is used to “shape the future more effectively” and to “[create]coherent futures” (Inayatullah, 2017, p1). The intention is to map the present, unpack an issue critically, and create a preferred future reconstructed from alternative worldviews and from multiple perspectives. This leads to transformed futures that integrate difference. It is a combination of the pull of the future, push of the present, and weight of history (Inayatullah, 2017, p6). Just as in the past, we currently find ourselves in a pandemic. How do we begin to make sense of the world we are in? “Epidemics are a category of disease that seem to hold up a mirror to human beings as to who we really are”; It reflects the relationship between people and their environment, raising questions about our ways of life (Chotiner, 2020). Metaphors are a way in which we can make concrete our imaginings, memories, and realities; they are devices with which we can play with concepts of time, blurring past, present, and future (Capo). Metaphors are meaning-making tools used in cognition and culture, shaping the way we act individually and collectively (Nerlich, 2020). In this essay I explore several dominant and emerging metaphors relating to the current pandemic, in the realms of society, technology, economics, environment, and politics. Each metaphor creates different realities, challenges, and opportunities. Social Realm COVID-19 has been labelled a plague. Both in religious terms – the uncontrollable mass spread of an unhealable disease – and in biological terms – a zoonotic transmission of disease from rodent to person. What results from this narrative is mass hysteria from those who fear the worst, an aura of shame around those infected, and the rise of body politics to control the contaminated and to contain the contagion. People become zombies trying to survive an apocalypse; it is the end of days. Like previous plagues, this pandemic is explained as either being a punishment for those who have wronged – morally, if from a religious perspective, or ethically, if from a biological perspective. Either society has transgressed to the point of no return (from a religious perspective), or particular populations are blamed and reprimanded and old prejudices are perpetuated (such as judging China for consuming particular animal products). The symbolism of the plague is used “to convey the suffering of the suffocation and atmosphere of terror and exile” (Zaretsky, 2020). If we were, instead, to view the pandemic as an opportunity for revolution or renaissance – to revive or renew our world – we could see the virus as triggering a turning point in history. This narrative establishes an element of empowerment, freedom, and consent. People become agents of change, contributing to the speed and depth of the transformation. The crisis becomes a catalyst for change, enabling us to dismantle old systems of superiors and subordinates. We are in this together. In viewing ourselves as global citizens in a shared process of being and becoming – with access to communal knowledge, collective consciousness, and an evolving social commons – we are presented with an invitation to transform wicked problems into wicked opportunities (Eggers & Muoio, 2015). An example of this is the call for an African Health Organisation that embraces – rather than undermines – traditional medicine from the continent (SABC News, 2020). It is not to say that WHO should be replaced or dominated by THO (Traditional Healers’ Organisation), but rather that a collaborative relationship be formed to develop new approaches to crises. It is about leveraging Africa’s strengths, not straining its weak points in favour of a homogenised, westernised method (Senbanjo, 2020). Technological Realm If all the world’s a stage, as Shakespeare proclaimed, then we must be on The Truman Show. It is as if someone has hit the pause button; everything has slowed down. “Collectively we are witnessing a global phenomenon that has people everywhere staying home, slowing down, and witnessing a global pause during this pandemic” (Devaney, 2020). While we seek to digitalise everything – the way we work, socialise, learn – prospects of compromised privacy and enhanced monitoring of our online lives becomes a growing concern: “the rise and spread of digital surveillance enabled by artificial intelligence” (Wright, 2020). This brings into question the agency of the individual and the authority of the state. We have long observed the growing power of media in swaying or formulating opinion, as well as gathering data and information for commercial or political benefit (Confessore, 2018). Viewing the virus as a glitch or technical error seems to justify ‘rebooting’ the system. In this narrative, AI will save us, even if it is at a cost. “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next one” (Roy, 2020). This suspended moment, from this angle, becomes a time of transition; a liminal space between reality and a dream-state. It becomes an opportunity to take a breath, put future scenarios on hold, experiment with possibilities, consider the legacy we want to leave behind, and take in the present moment, before we are transported into the new world. Doing so requires decentralised and autonomous control, as well as open source products and collaborative platforms as we co-create futures. An example of this is the vast number of online conferences and symposiums – often made freely available to all with internet access – that have erupted from all parts of the globe. While we may have put our personal lives on pause, we are far more globally connected than we ever were before. Just look at the global foresight summit hosted by FFWD titled ‘The Great Pause’. There were attendees from over 100 countries and speakers each with a one-hour timeslot over a 72-hour period. Economic Realm When a severe storm approaches, with little time to think or react, an instinctual response it to act quickly; to take shelter from the rain, and consider the cost of destruction after you have secured your safety. Every moment counts. Similarly, in a ship rescue, there are often those who want to contribute, but are unable to and can create confusion. Pandemic shock brings about collective trauma, crisis capitalism, and imagination paralysis (Klein, 2007). It is easy to decline into a bleak state of despair and dysfunction when in a disaster. Some are more vulnerable than others – we are not all in the same boat or equipped with the same tools to navigate Lightning bolts of disruption and tidal waves of change. Some make it to shore while others are rendered invisible amidst the throws of vicious and virtuous cycles that deepen inequality. In a state of emergency, a utilitarian approach is often taken to ensure the immediate survival of many, even if extreme measures need to be taken. However, “once the Hammer is in place and the outbreak is controlled, the second phase begins: the Dance” (Pueyo, 2020). If we view the pandemic as a dance and the future as our dance partner, it becomes a give and take relationship of synchronisation, harmony, and collaboration. People are no longer captives to the captains of their fate, but rather dance to their own tune and choreograph their own routine. An example of this is South Africa’s declaring of the pandemic as a national disaster and focusing on providing food parcels for the hungry, shelter for the homeless, and relief funds for the financially-strained businesses. However, in its efforts to contain the spread of fear, to perform damage control, and to ‘flatten the curve’, its extended lockdown has come across as Draconian, or unnecessarily harsh. Many citizens argue that instead of moving to the dance phase of its strategy, leadership is repeatedly hammering the same nail. Or so it seems. While the spread of the virus is relentless – particularly across the nation’s informal settlements and informal economy – leadership has put out fires elsewhere. In banning the purchase of alcohol during lockdown, the country has seen a significant decline in alcohol-related casualties (including car accidents and domestic violence). The pandemic does not operate in isolation, nor is it linear in its movements. It requires a hammer and dance approach to respond, adapt, and anticipate shadow crises, chain reactions, and satellite events. Environmental Realm Countries declaring the pandemic a national disaster are putting into place regulations and measures of control – such as providing tax relief, setting up temporary housing, responding to distress signals, and offering financial aid – to minimise damage. The virus in this narrative is perceived to be a disruption caused by natural processes beyond human control, but owing to destructive human influence. Thousands of years ago, communities the world over acknowledged the interconnected relationship between nature and culture. If there was turmoil or conflict in society, it would appear in nature – drought, fire, disease. Nature was seen to be this self-reproducing entity, not to be disturbed or exploited. It is only more recently that the western world made this ‘discovery’ – the Anthropocene. The disaster metaphor paints a picture of humanity as victims or survivors, volunteers or philanthropists. While disaster management is a necessary temporary measure in extreme circumstances, there needs to be a journey of healing following the experience of loss, pain, and grief. It requires consideration for both movements on the surface and the undercurrents below; how deep do these problems run? Life in pandemic – like a river – has moments of slow calm and quick turbulence, clear shallows and murky deepness, free-flowing paths and diverging streams. Developing a dynamic map with which we can navigate uncertain terrain, anticipate obstacles, and plot strategic directions would make us explorers – not survivors – of a new world, connecting with others along the way. An example of this is how “New Zealand has offered a model response of empathy, clarity and trust in science” (BBC News, 2020). Instead of identifying an enemy and establishing a plan of attack, New Zealand encouraged unity and working together. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s message stayed consistent and clear: “Be Strong. Be Kind”, and so the country was a given a map with which it could navigate the course of the river it found itself on. Political Realm Many the world over seem to be at war. They are united against a common enemy, fighting for a common goal: eliminate the threat to human life and national security, even if it is by violent or aggressive means. In this narrative, citizens become soldiers. It is their duty to fight for their country, protect its borders, and obey orders from power-wielding leaders. Often these power dynamics go unchecked, restrictions are enforced unquestioned, and harm in inflicted unnoticed. As many nations go into what has been termed ‘lockdown’, one cannot help but feel criminalised. Curfews, restrictions, bans – it starts to feel a lot like imprisonment. If we were to rather invoke the idea of a game of chess, we start to see the virus as a challenge, rather than a cage. In applying logic and strategy to develop a game plan, people enhance their mental mastery and are better prepared for future scenarios that may emerge. As players, people alternate between seemingly unassuming moves, taking risks, and making strategic decisions for the end-game – before taking on the next challenge. An example of the war metaphor is US President Trump’s naming the ‘China virus’ a public enemy which must be defeated. Increased border protection, rising nationalism, and enforced hero-narratives make it difficult for people to fight back and remain autonomous. When it comes to thinking things through in the form of a game of chess, we can apply Inayatullah and Black’s (2020) definition of foresight as “the capacity to anticipate tomorrow’s problems and [to]act today”. They argue that COVID-19 is neither a black swan nor a zombie apocalypse; it was neither unpredictable nor a total surprise. Instead of focusing on what was missed or unseen, we should, they urge, prepare for the next pandemic. Conclusion “The main point is that narrative, how we describe the world structures our possibilities, what options we can see, what is possible for us to create” (Inayatullah, 2020). Many of the dominant pandemic metaphors encourage destructive discourses and promote ideas of separation or superiority. The emerging metaphors in this essay are proposed as transformational alternatives that promote interconnectedness and a process of change. There are different ways of seeing, framing, and being in the world. The language we use and the metaphors we apply, shape the way we experience reality, imagine possibility, and take on responsibility. Originally published on JFS

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

MARGUERITE COETZEE

ANTHROPOLOGIST | ARTIST | FUTURIST CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed